Slow-Cooked Community

The Bennington student founders of the Slow Cooked Movement discuss how they brought community, nutrition, and local farms together during this Field Work Term.

Updated: June 2021

The Slow Cooked Movement Recipe Book, designed by Akanchya Maskay '21, is now available! Download your copy.

During January and February, many Bennington students depart campus for Field Work Term internships and learning experiences across the world. However, a significant number of students opt to stay on campus during this time—particularly this year, when COVID-19 restrictions have made travel difficult, and Field Work Term employers shifted many internship experiences to a remote format.

During January and February, many Bennington students depart campus for Field Work Term internships and learning experiences across the world. However, a significant number of students opt to stay on campus during this time—particularly this year, when COVID-19 restrictions have made travel difficult, and Field Work Term employers shifted many internship experiences to a remote format.

Altogether, over 100 students remained on campus during Field Work Term this year—and though their remaining on Bennington’s campus was best for public health, social distancing during the winter months posed its own challenges.

“People feel very alone, in general,” said Ulyana Shkel ’23. “Campus life is calm and slower paced—which was great when winter break first started, and people started reading their own books, doing things for themselves, and having time and space to enjoy life. But after a couple weeks, it becomes routine.”

Throughout the Fall 2020 term, Shkel was attuned to the wellbeing of their peers and became aware that many students felt depleted in both body and soul. In addition to general feelings of sadness, anxiety, and isolation—all exacerbated because of the ongoing pandemic—the Dining Hall’s necessary adjustment away from communal serving was challenging for students. Due to lowered access to staffing, the Dining Hall had less of a capacity for cooking at its standard rate.

Toward the end of the term, Shkel emailed faculty member Yoko Inoue expressing these concerns and asking to meet.

“Yoko is an incredible person who is super supportive of student initiatives,” said Shkel. “I initially came to her without any idea of what to do; I just came to her with concerns, and she helped.”

Creating the Slow Cooked Movement

Inoue told Shkel about the Student Projects Fund, a resource provided as part of Bennington’s Andrew W. Mellon Foundation-supported grant to address food insecurity in Bennington County, and suggested that Shkel apply for a project grant to support student nutrition and well-being on campus over Field Work Term.

“Yoko told me about this grant and that she would help me write it,” said Shkel. “I’d never written a grant before, but somehow, especially with Yoko’s connections among students, everything came together.”

As luck would have it, three other students—Akanchya Maskay ’21, Jacqueline De Loos ’22, and Cass Skarka ’22—had also expressed interest in food, cooking, nutrition, and well-being on campus. Inoue included them in an email chain, from which point the group convened to begin work on a project grant.

“After discussing a bunch of potential projects, this idea of using a slow cooker came in,” said Cass Skarka ’22, whose work was instrumental to structuring the grant proposal and who co-wrote it with Inoue and Slow Cooked Movement students. “In one of Yoko’s classes, we had looked at a project that’s happening with RiseVT Bennington County, which is distributing donated crockpots to distribute them to families in need. Since crockpots only need an outlet to operate, you can do so much with them.

The group also expanded the conversation to incorporate local farmers and producers, who often struggle with supply and demand during the winter months. By the end of the group’s deliberations, a project had come together: the Slow Cooked Movement—a means of creating community by providing nutritious food to students on campus, while also engaging with local farms.

Slow Cooked Movement was modeled after a 2020 summertime farmstand held for off-campus students at Paran Creek apartments. Inoue—who had been awarded $1,500 from a Residency Unlimited Food Futures grant—used the award to arrange a weekly fresh produce package with Wildstone Farm in Pownal.

Working with Skarka and Bennington students Sbobo Ndlangamandla '21 and Desire Chimanikire ’23, the group created a free weekly farmstand, featuring seasonal offerings from Wildstone Farm, for Bennington students who were staying in Paran Creek through summer 2020.

Inoue heard of the excitement from participating students and took note of how that project’s success stemmed from the intersection of fresh, local food and the opportunity to gather as a community.

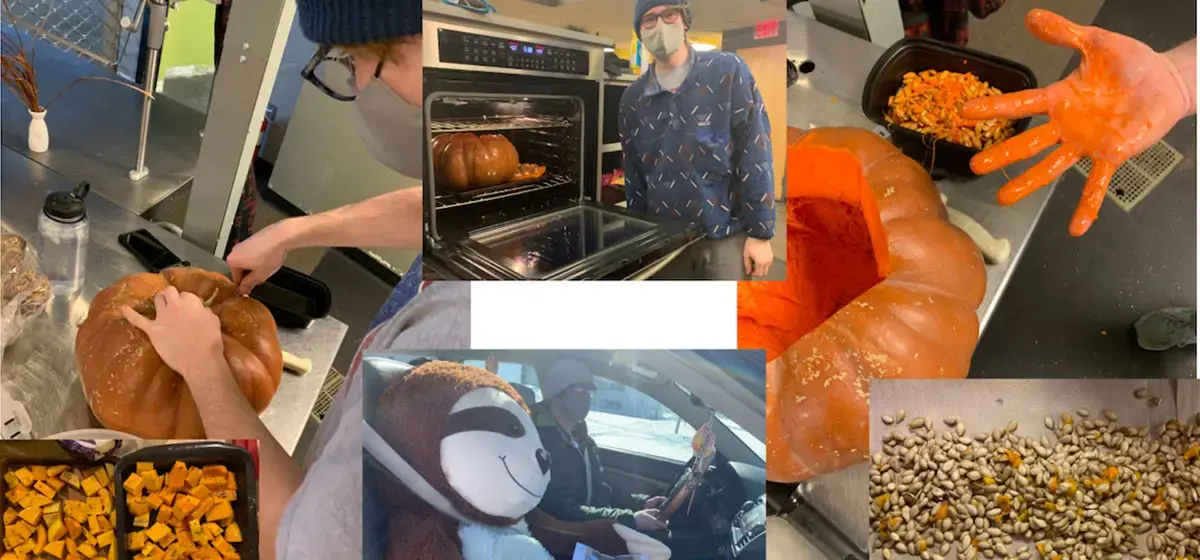

The Paran Creek Farmstand became the inspiration for the Slow Cooked Movement, which was ultimately awarded a Student Projects Fund grant of $2,500. This grant helped create four sets of kitchen tool kits, each of which included a slow cooker-pressure cooker combo, a good knife set, a cutting board, a hand-held blender, and a ladle in a container. The funding also enabled students to purchase fresh food sourced exclusively from local farms and food producers.

Throughout Field Work Term, the four conveners met with faculty supervisor Yoko Inoue and Community Engagement Field Work Term intern volunteers on Tuesdays. During the week, the group worked to cultivate relationships with local farmers—examining the regional food asset map collaboratively created by the Town of Bennington, Bennington County Regional Commission, and Food Systems Practitioner-in-Residence Ben Hall ’04 and faculty member Tatiana Abatemarco, as well as students in their respective classes—then cold calling and emailing area producers to explain the project and see what they had available.

“It’s been cool to make these connections, and the response has been welcoming and great,” said Skarka. “Being able to talk with these farmers on a personal level and going to pick up food from their farms involves not only meeting farmers, but building relationships and learning from them. It’s not a one-and-done interaction; the connections we’re working to make are ones that Bennington can utilize in the future.”

“Bennington is close to so many local farms, but students often limit our food to Walmart or Hannaford,” said Akanchya Maskay ’21. “The more we’re in this project, the more we realize that we have so much produce around and such lovely farmers. And even if we’re providing students with one nutritious meal a day, it’s still something that comes from the heart.”

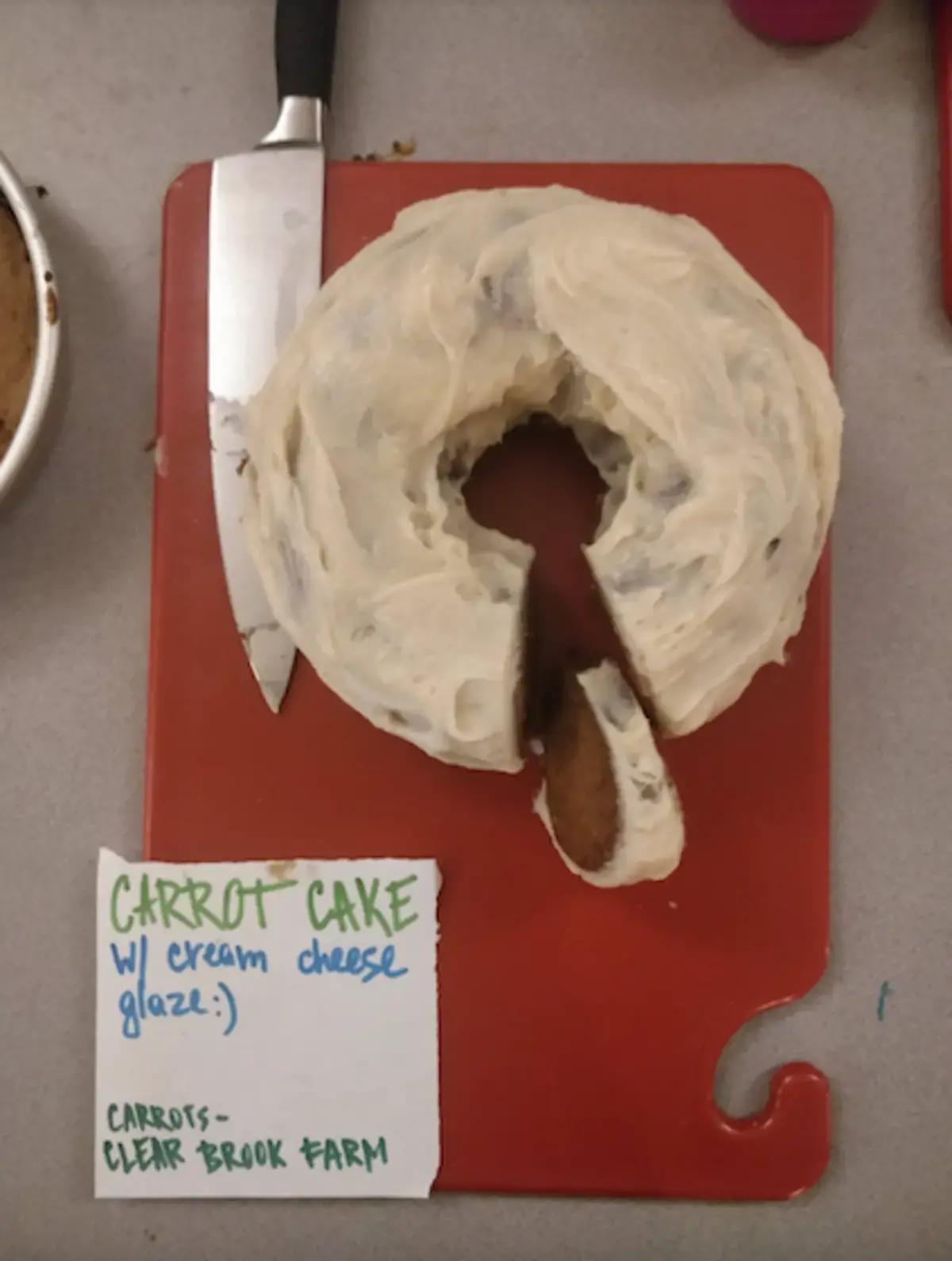

Throughout Field Work Term, participating farms included Clear Brook Farm, Saunders Family Farm, True Love Farm, and Wayward Goose Farm, which provided the project organizers with a robust weekly variety of meat, dairy products, and produce.

“Our own limitations in cooking got pushed,” said Jacqueline De Loos ’22. “When we got the ingredients, we didn’t give farmers a specific list for recipes—we asked, ‘What do you have? What are you getting rid of?’”

Innovation and Community

The resulting goodie bags of supplies—combined with the slow-cooker format for making soups, which was a new tool to each of the students—made for creatively satisfying and super delicious dishes.

“This project also allows us to explore our different cultures through dishes using a slow cooker—but the process is new for each of us,” said Maskay. “Cooking traditional dishes, or even ones we’re used to, is completely different while using a slow cooker.”

“At one point, we got a whole bag of sunchokes [donated by Alexis Elton of Rockland Farm Alliance in New City, New York, as part of the “Project Greens” program, created to help those with food insecurity during the Covid-19 pandemic]—I had no clue what those were, but I turned them into this soup that tastes like artichoke,” said De Loos. “It was a cool process for me, taking this vegetable I'd never seen or heard of, and then all of sudden, it was transformed into a big bowl of soup that could be shared with everyone.”

“Akanchya once made beef heart soup—it was like a beef stew with chunks of beef heart,” said Shkel. “I usually don’t eat much meat, especially if I don’t know where that meat comes from, so this project became an incredible opportunity to eat meat, which felt so healthy and good for everything in my body.“

“We had a delivery that included pork neck, which I’ve never worked with before,” said Skarka. “But I had a friend on campus from Bosnia [Mirza Cevra ‘22] who talked about his grandmother’s goulash. So I got to Facetime with her, and we made her recipe using pork neck and local Vermont vegetables. In ways like that, this project has become a big Skillshare, as well.”

Every Saturday, the Slow Cooked Movement’s weekly efforts culminated in a community meal, open to all students on campus, which tended to include both vegan and meat-based options. Akanchya and De Loos created a project logo that they used for stickers, distributing these weekly for promotional purposes as well.

“When we launched the project, it was interesting to see how the work and preparation we did online was suddenly in a physical space with people in it,” said Shkel. “It was beautiful for me to see all our work online being actualized in a physical sense.”

“We held the first meal outside of Commons—it was freezing, but people still showed up!” said Skarka. “It was incredible, though, because there’s nothing better than being outside with a warm bowl of soup.”

By the project’s third week, however, the Slow Cooked Movement was granted a new home in the Student Center—an area that allowed students to cook together, provided ample freezer and storage room, and was ideally spaced to allow students to safely gather and eat indoors.

As the project grew, “more and more people came and talked about it—and not only did they want to eat, but they wanted to cook and help,” said Skarka.

“The student workers in Student Life over Field Work Term have promoted and shared the project, and they’ve helped with logistics,” said Shkel. “Later on, it would be exciting to connect this project with Student Life events, so people could come together for an activity and a meal.”

Indeed, the campus came together to help in unexpected and wonderful ways. Chef Steve had planned to transform Roz’s cafe into a grocery store for FWT students remaining on campus, and he offered a knife skills workshop to help empower the students to gain skills and knowledge, which could all be shared with the community. And to reciprocate the help provided by student interns in Student Life, SCM members provided homemade snacks to their movie nights. Campus Safety lended a helping hand by donating a driver to help mobilize people from Paran Creek.

From the group’s first brainstorming session to the last Field Work Term’s worth of community meals, the Slow Cooked Movement has already evolved and accomplished a great deal. As for its organizers, all of them hope to see the project evolve to create a lasting awareness on campus of the importance of connecting food, community, and local resources.

“I know that the farmers we’ve talked to, we’ve talked to them in a way to continue working with them in the future,” said Maskay. “Because of how this grant has been focused on the slow cooker, it’s given a model to bring in more of the community engagement around food security on campus and the community. But depending on who works on future projects, this can continue to change according to who's involved, and it will grow.”

“We’d like to pass on the kitchen kits and slow cookers,” said De Loos. “But ultimately, we’ll just see how this evolves over time. The project has helped create a sense of normalcy. It’s easy to think that we’re incapable of continuing projects because of COVID-19, but we’ve actually been given a blank canvas that we’re able to fill in in a way that makes sense and is innovative. That has been a huge part of the goal here.”

Stay tuned for an upcoming zine featuring recipes! In the meantime, check out a few sample recipes!

The Slow Cooked Movement organizers wish to thank the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; faculty supervisor Yoko Inoue; Shannon Barsotti, Director of Community Development for the Town of Bennington; Food Systems Practitioner-in-Residence Ben Hall ’04; staff members Chef Steve Bohrer, Ken Collamore, Angel Kwasniak, and Meredith McCoy; the Student Life Office, and particularly the Student Life Field Work Term interns for their promotional help; and President Laura Walker and the Bennington College President’s Office.