Extending Uncertainty: An Interview with Pat Adams

By Anne Thompson

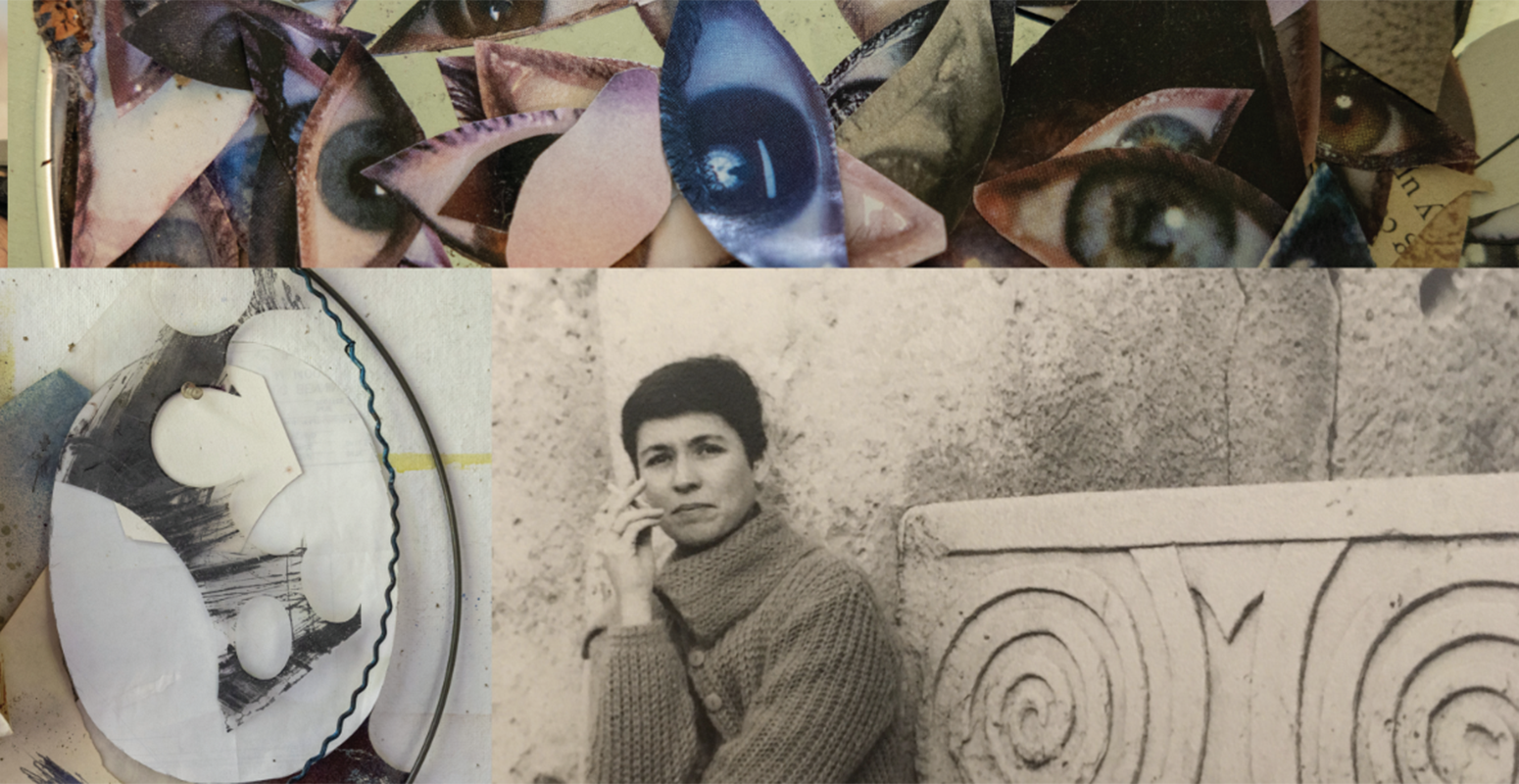

Pat Adams was born in 1928 and raised in Stockton, California. She studied painting at the University of California, Berkeley, and took classes at the California College of Arts and Crafts, the College of the Pacific, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Brooklyn Museum Art School. She received her first solo exhibition in 1954 at the Korman Gallery—later to be renamed the Zabriskie Gallery—which represented her until 2018.

She taught at Bennington for more than thirty years and also at Yale and the Rhode Island School of Design, among numerous other institutions across the country. Her students describe her as “a life-changing teacher.” Many thank her for transforming their notion of what it means to be an artist.

Adams received notable awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Academy of Arts and Letters, the National Academy of Design, and the College Art Association. In 1995, she was awarded the Vermont Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. Her work has been the subject of more than fifty solo exhibitions. Anne Thompson, director and curator of the Suzanne Lemberg Usdan Gallery at Bennington College, sat down with Adams in her home studio in Bennington. Thompson’s and Adams’ conversation revealed Adams’ sense of herself as a painter, her teaching philosophy, and her hopes for humanity.

AT: You taught at Bennington for almost 30 years, and after that, at the Yale School of Art. How would you describe your teaching approach?

PA: I had two goals. First, to give students the language by which they could discuss their work. When I was [a student] at Berkeley, I took a course in literary criticism, and I was astonished at the language they had developed. And when I was teaching, I could see there was a true lack. So developing a language was important. And my other goal was to increase the sensuous aspect of their experience. Students would say to me, I already know about color, line, texture. They may have identified where it occurred, but they did not have a sense of it. To be an artist, you have to register something more deeply. And so my assignments all aimed to develop an increased sensuous self to put back into their efforts.

AT: Language is important within your own approach to painting, in the specificity of your titles and also some idiosyncratic terms you use to discuss your process. I’m thinking especially of “toward-ness” and the “not as yet.” What do these terms mean to you?

PA: I am not a one-shot painter. Some paintings take a couple of years—and they don’t take a couple of years because I’m not working. I have them around, and I study them. And so they’re “not as yet,” but something is coming. I’m waiting to see what the painting needs. I’m painting, and I’m looking at something. Suddenly, I’ll have a strong sensation. I’ll feel that painting. It tells me it wants a purple that has a little brown and a little pink in it. There’s a capacity to prolong uncertainty, to not know what’s going to happen. To extend that uncertainty is something I’m very serious about.

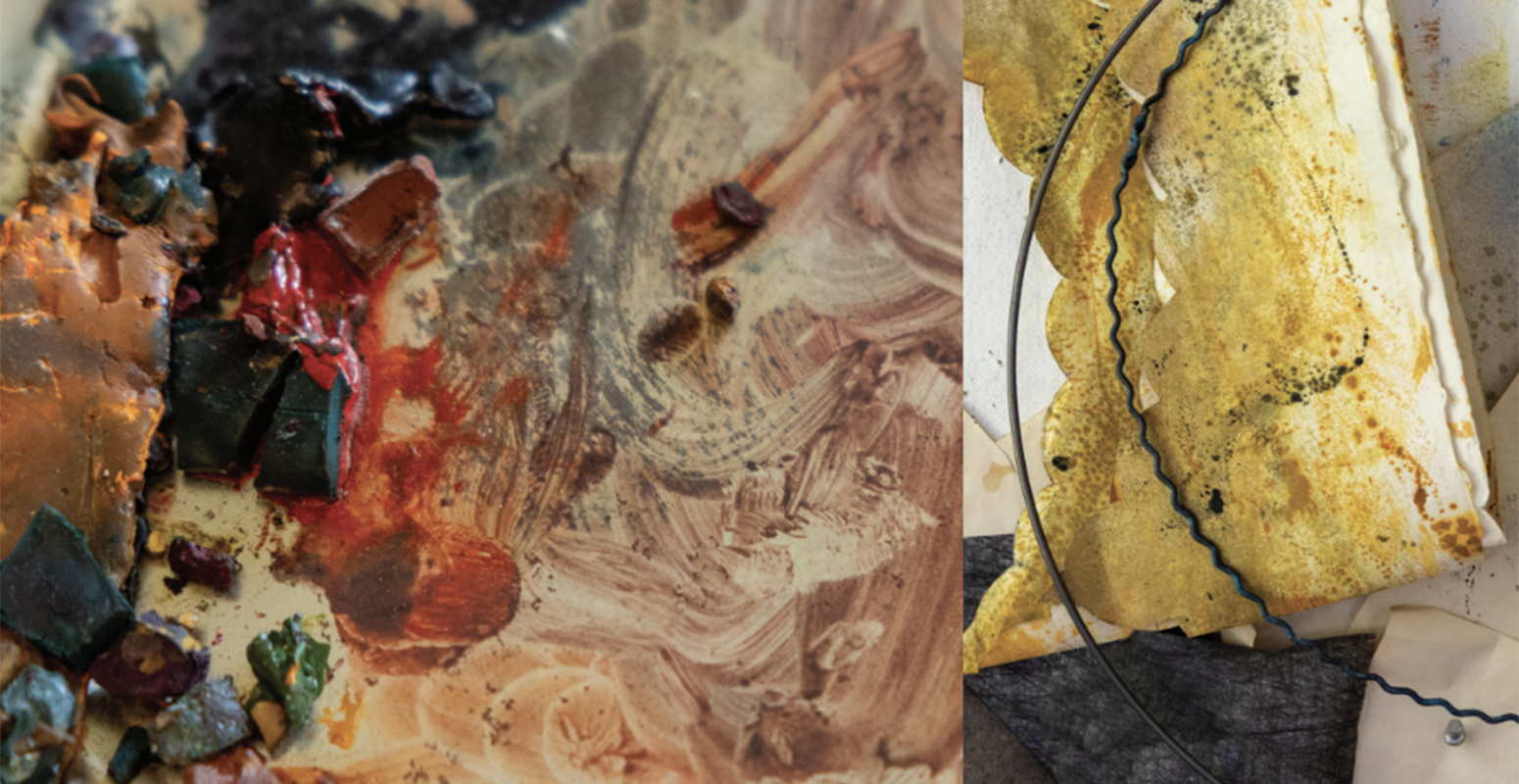

AT: We’re sitting in a studio you recently set up in your house, where you’ve been making collages and small paintings on photographs. It’s like a satellite to the large studio outside on the grounds of your property. At age 96, how do you approach your studio practice?

PA: I don’t use the word.

AT: Practice? Oh, okay. Why not?

PA: What does practice mean? Practice is a series of developed skills, and it’s known. Art is not, at least my art is not about “to know.” My painting is about quiddities, what-nesses, In fact, I dream about this—figuring out, how can I do this? How can I do that? Do I need a template for this kind of curve? How much of an arc do I want? Do I want to reverse those two arcs? I think we should just celebrate that we have all of these vast, delicious, formal possibilities.

AT: Over the years, since the 1970s into today, some critics have described your work—in a positive way—as hard to categorize. You seem to have simultaneously embraced and rejected the modernist dictates, such as flatness, that dominated the scene when you were coming up in the 1950s and 60s. Looking back, what was your relationship to those evolving art movements, abstract expressionism and minimalism in particular?

PA: I love the Sanskrit word Anekāntavāda, which means many-sided-ness. I’ve never felt you had to develop a style that overthrew the previous style, that you should overthrow this and argue against that. I’ve always felt that it was almost like Cinderella—will your work fit into the shoe of the current style? I’m disinterested totally in that point of view. I’m looking for a kind of accuracy. Is this accurate in terms of my understanding of things? I think my whole life is a form of evidence of living and looking and marking and relating the interactions of different little pieces of paper or little blocks of ink.

It’s an enormous pleasure trying to apprehend what existence is about.

AT: Before she died in 2023, your former Bennington student Cora Cohen gave a painting to the College in your honor, and I had the privilege of choosing the painting. Cora encouraged me to pick a big “macho” painting that would take up a lot of space. It was her sense that, as a woman in the art world and academia, you didn’t get the respect you deserved. What are your thoughts on that?

PA: It’s a big question. I had a very solid sense of myself as an artist because I had always painted and had regard from many people. I never felt that I was being diminished. I lectured and showed my work all across the continent. And wherever I went, I was treated very decently, except in one place in Kentucky. And the students rose up and told this man, please let her talk. They wanted to hear what I was going to say. So that worked out very well. But I do feel different men definitely have problems with women, and I don’t know what that is. In a review of my show of the big paintings, one man spoke of how I “imposed” my forms on the canvas. What a curious word. I can only think about him and ask what, really, was he feeling?

AT: You’re referring to your 2023 show of large-scale works at Alexandre Gallery, in New York, where you also had a show earlier this year. You’ve consistently been showing your work, almost every two years, since your first exhibit in 1953, mostly in New York. What has it been like to be an artist exhibiting in the city but not living there?

PA: I love New York. I did not leave California to come to Bennington. But circumstances change. I have a family—two sons, three sensational grandsons. A lot of my experience over my whole life has been that I didn’t have time to “hang out."

AT: Being in New York as an artist can involve some hanging out.

PA: It’s true. We had dancing parties at the loft in the fifties, and once I came up here [to Vermont], we did have a couple of dances when [sculptor and Bennington faculty member] David Smith came over and others came over. But I was so busy being a mother, a teacher, a painter. I could not just do what others, who were not so involved in life but more involved in enjoying each other, were doing.

AT: You were incredibly influential as a teacher. For you, what was your biggest contribution to Bennington?

PA: Well, the whole notion of students having a corner. And this came from my own life experience. I did not see a studio until 1952. And I wanted these students, particularly the upperclassmen, to know what a studio could mean. So I devised studios with movable walls that could form corners, one student would work here, another would work there. And the experience I wanted to provide was that as they walked into the corner, that was their world. That was the collection, the marking, the sketches, postcards, whatever it was. So they began to identify and develop their own vision.

AT: In your lectures and writing, you’ve discussed the endurance of painting in the face of trends that declared it to be dead or irrelevant. What are the stakes for painting today?

PA: Early homo sapiens as a species felt the urge to mark something. They used soot, grease.

In each person, there is a form of utterance waiting to come forward.

And anytime you shut off the unconscious, anytime you shut down, you are diminishing the future of the species. I’m very concerned about the use of so much artificial intelligence. There’s something called homeostasis equilibrium. How do we achieve "equilibrium” if we ignore whole sections of our embodiment or personality? If we don’t have the pleasure and the invention and the freedom that art contains, we’re diminishing the human species.

AT: Do you have any advice for young artists?

PA: They need to recognize themselves. They need to begin to see what their work means to them, to try to deepen in every way they can, to have the whole sensory embodiment of art. And not to be involved in too much hearsay. I feel that you can listen to other people and, of course, you read everything you can. But your most important thing is to try to recognize what’s emerging.