Projection, Protection, and Priestessing

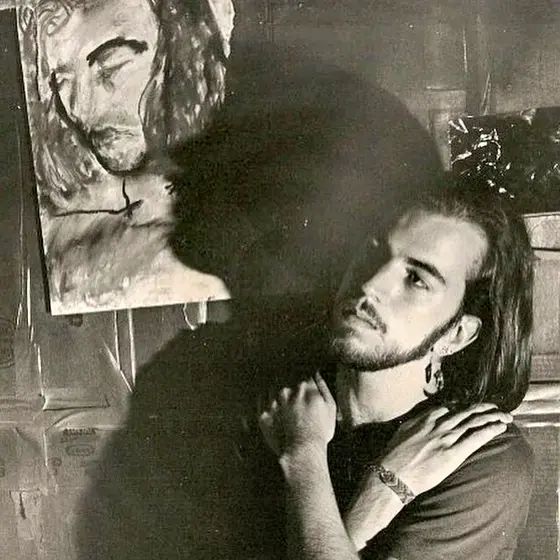

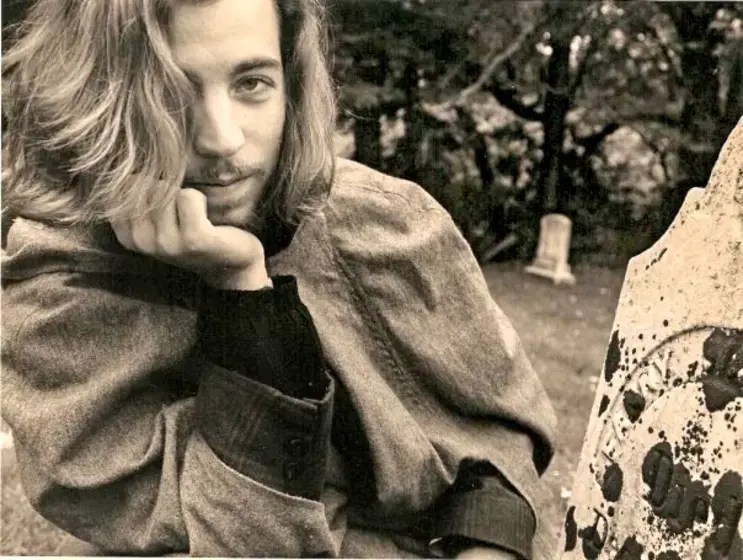

Met Gala Magic from Michael Sylvan Robinson '89

By Mary Brothers '22

When Michael Sylvan Robinson '89 got the call that they had been commissioned to make a piece of art for theater director Jordan Roth to wear to this year’s Met Gala, one of the first emotions to set in was panic.

“I never really believed it was going to be mine until long after everyone else knew it was going to be mine,” said Robinson. “I thought to myself, now I have it, I have six or seven weeks to make a Met Gala outfit. When I knew I needed help on this project, the first person I turned to was a Bennington friend.”

That Bennington friend was Valerie Marcus Ramshur '89, acclaimed costume designer and Head of Costume Design Training at MGSA Rutgers University.

“When I knew I got the gig, I reached out to Valerie, who was one of my dearest friends from the Bennington years,” said Robinson. “I called her and said, ‘Listen, I can’t really talk about it, but I needed assistance two weeks ago. I need people I can work with, and I’d rather work with recent alumni or students.’”

As an arts educator, Robinson felt strongly about using this opportunity to support young people in their pursuit of their work in the world. Robinson worked closely with three recent graduates and one current student to create the piece along with Bill Bull, an experienced dressmaker and tailor for Vogue.

“This is a very different story,” said Robinson. “It’s not the way that a ‘normal’ Met Gala outfit is created. This was something that came out of very different hands and from a different collaborative process.”

Protection from Projection

Robinson credits a large part of Roth’s decision to work with them on the Met Gala piece to Robinson’s unique focus on gender and gender identity.

“One of the reasons that Jordan and I connected so strongly was that, for me, there have been times in my life, particularly when I was at Bennington, where we would now describe me as a genderqueer or nonbinary person,” said Robinson. “Roth was looking for a garment that would come out of somewhere different. My activism and my sense of being an arts educator and a person in the world who’s making art from a more community-based approach, was one of the ingredients that Roth was trying to mix into what is often an exclusive category of experience.”

Roth and Robinson then went on to collaborate on a piece that fully expressed identity, while simultaneously rejecting the projections that people cast on a person who chooses to rebel against the constructs of traditionally gendered clothing.

As a genderqueer artist, Robinson knows all too well society’s tendency to take gender-fluid fashion as “an opportunity to both treat you as exotic, or other or, to ignore or disregard your work.”

“I thought a lot about the idea of, could I offer some sort of protection from projection?” said Robinson. “All those eyes, the different eyes, the use of the evil eye, were a way of saying, ‘I know you see me, but also I’m not taking on your projections. I’m wearing this because this is what I want to be wearing in the world.’”

Interestingly enough, this was not the first time Robinson had a piece of artwork shown at the Met. One of Robinson’s first jobs out of Bennington was in the museum’s retail department selling jewelry, where they had the opportunity to showcase a piece of art as part of the annual employee art show.

“The first time any visual artwork of mine ever showed on the wall was in the nonpublic gallery, followed by a reception where the Met Gala dinner takes place,” said Robinson.

As they created the piece for Jordan Roth, Robinson found clever ways to pay tribute to that experience by including photos of statues they had previously sketched during their lunch breaks at the Met.

“Thirty years later, my wearable art walked back,” said Robinson.

Activism, Healing, and Remembrance

Now, as the world begins to become more accepting of different gender expressions, Robinson reflects on how their time at Bennington contributed to their ability to find freedom in fluidity.

“I spent a lot of my Bennington years both deliberately gender noncomforming or androgynously dressed,” said Robinson “I wore dresses to dance class and was known for being really on the far side of gender boundaries throughout my whole process of being on that campus. For the most part, Bennington and my peers really loved me for that.”

However, after graduating from Bennington, Robinson had to find a way to adapt to a less-accepting world without compromising their identity, an ordeal that significantly impacts their artistic process to this day.

“One of the things that happened as I left Bennington was that the world was not as ready for me in the way that I had been safe and encouraged on campus,” said Robinson. “I reentered New York at the height of the AIDS crisis as a young queer person really in harm’s way. It’s an unimaginable way of arriving in the world as a young person at a time where your friends don’t live to thirty. A lot of my work continues to think about trauma, healing, remembrance.”

A close friend of Eric Ginman ‘92, Robinson used this emphasis on remembrance and memorialization in their work to create a wearable art piece in honor of Ginman for the 2019 Bennington 24 Hour Plays. It was the first wearable piece that Robinson had made to be put back on someone other than themselves.

“Up until that point, I had been saying to people, I’m not making costumes anymore. The only wearable art I’m making is if I want to wear it in action,” said Robinson. “I’m not going to go back to the body; it’s really about the absence of the body.”

Despite these previous assertions, Robinson found the experience impactful enough to return to the body as inspiration for garment design.

“I don’t know that if I hadn't done the 24 Hour Plays, I would have ended up in the Met Gala. I really mean it,” said Robinson “I’m a big supporter and contributor to the Spencer Cox Activist Fund. I do so in memory of Eric every time I make a gift in that fund. That work is really embedded in what I created to be worn at the Met Gala. It comes out of that same knowledge of history of queerness, of gender, of shifting understanding of self.”

As someone who has been working in queer activism for over thirty years, Robinson has a lot of wisdom to share with younger artists about the importance of care of self in protest and in art.

“There’s also a way in which being an activist is about being careful with each other and taking care of each other,” said Robinson.

Robinson encourages young artists to ask themselves as part of their process. “What do I need that stays on the inside? Are there things that I’m going to say more personally in an inner way or reckon with for myself? Do I need to tell this whole story? Do I need to explain the dance? Or, would a simpler statement be enough for people to be able to see themselves and more, rather than me telling them exactly what it is they’re supposed to be seeing or experiencing?”

Despite this recent foray into the luxurious world of haute couture, Robinson still finds solace in remembering and returning to their origins, recognizing that “there’s still an awful lot of drag queen mixed into my sense of materials.”

“I’m doing a fair number of interviews,” said Robinson. “There is something about this return [to Bennington] that is very special for me as well. To say, hey, this genderqueer designer started in a very particular place.”