From Civil Rights to Civil Conversations

Gail Hirschorn Evans ’63 worked at the White House in the Office of the Special Counsel to the President during the Lyndon Johnson administration and was instrumental in the creation of the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity and the 1965 Civil Rights Act. Decades later she is still challenging our biases. By Jeva Lange ’15

Here is your result.

The words are written in black, bolded letters across the top of my computer screen. The next line says: “Your data suggests a strong automatic association for ‘male’ with ‘science’ and ‘female’ with ‘liberal arts.’”

The sinking feeling in my chest is as immediate and crushing as if I have received an F on an algebra test. Sexist? Me? As a West-Coast-raised, Women’s March-protesting feminist, I am shaken to my core. Where did I start internalizing this? And even more distressing, when?

I took the Harvard Implicit Association Test at the direction of Gail Hirschorn Evans ’63, who has spent nearly a lifetime trying to understand just this. As she tells me on the phone, “People who consider themselves great liberals say things like, ‘I don’t see race. I see the person.’ That’s BS. It’s just not true. ‘I don’t see gender in my hiring, I see the quality of the person and their accomplishments.’ That’s not true.”

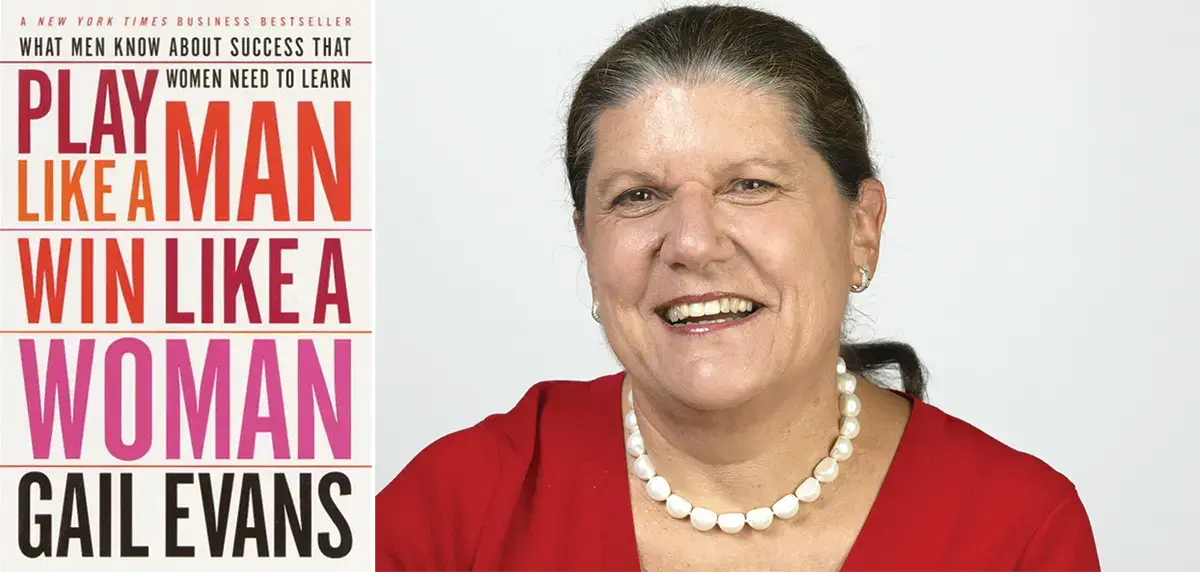

After having spent decades working in male-dominated industries, Evans knows what she is talking about. Evans began at CNN in 1980 and by the time she retired in 2001, she was the executive vice president of the entire newsgroup. In 2000, she used her experience in the business world to publish a bestseller titled Play Like a Man, Win Like a Woman: What Men Know About Success That Women Need to Learn, which lays out in conversational terms how women can tweak their thinking in order to make it to the top.

As Evans notes, “At the end of my career, after I wrote Play Like a Man, Win Like a Woman, I was giving a speech one day and I said, ‘Oh, isn’t that interesting? My career has actually been circular.’ I never even thought about it.”

That circle begins back when Evans was in fourth grade, when she read a biography of Clare Boothe Luce, the first woman to be appointed to a major ambassadorial post. “I read this book and was like, ‘Oh, look, a woman could do that!’” Evans recalled. “I think it sort of inspired me."

Luce sparked Evans’ passion for politics, and all the debate and ruckus that comes with it. “My mother always used to scream at me, ‘Just remember, it took Republican money to make you a parlor pink!’” said Evans, laughing. By the time she was in college, Evans was interning for a woman at the Asia Society in New York, who eventually connected her with a man named William Fitts Ryan. Ryan, as it turned out, was planning to run for the House of Representatives. He won, and Evans worked for him during every Field Work Term and summer that followed until graduation.

Then she moved to Washington.

It was the early 1960s, and America was roiling in the civil rights conflict. After working on the staffs of two other Congressmen, though, Evans began to get restless—and ambitious. “Anytime I went to any parties or did anything in Washington, I would say, ‘If anybody knows anybody who’s looking for somebody at the White House, I’m game and available.’”

That is how Evans eventually landed in the Office of the Special Counsel to the President during the Johnson administration.

Evans took to it—she loved the challenge and didn’t mind the long hours that came with the job, either.

There were always either personality disasters or legal disasters or political disasters, and you just had to figure out the best way to handle it,” she says with surprising enthusiasm.

Most of her work at the time centered on research for the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity. She describes an atmosphere where, while it was predominantly men talking about the legislation in the congressional chambers, it was ambitious young women who fueled the research behind their landmark bills.

“There’s a lot of hard work and a lot of research that goes into creating those kinds of things,” Evans said. “Then there’s the glory part at the end, where the president and everybody puts it together and sells it. But to get there, with the right language, with the right verb tenses, to make sure it will politically hold up—that takes a lot of staff time.”

So whenever a question would come up—was this the right language? Was there a historical precedent for that?—Evans or one of her three or four colleagues in the office would rush off to find out.

A lot of Evans’ energy went toward getting the business community on board with the equal opportunity legislation: “Part of what you did was help identify who are the business leaders who need to be talked to, how do they need to be talked

to, what are their interests, where are the sweet spots with all of them,” Evans says. “Literally—and I was a young nobody, you would do anything from plan the party to do the research about the people who were coming, and then if one of the waiters didn’t show up, you’d pass the drinks.”

But while the legislation would include the protection of women in its language, at the time it was much more centered on minorities. “I don’t even remember much discussion about women,” Evans admits. “I actually think I was probably very naïve. I believed if you were smart and you worked hard and you knew what you were doing and you understood politics, then opportunities for women were not going to be that different than for men. It was not until I got deep into my career that I realized the higher I went, how few other women there were.”

In fact, Evans believes that in the decades since the landmark civil rights legislation was signed, the discrimination against women and minorities has become increasingly subtle. Soon enough, she says, Americans forgot how to talk about issues of race and gender altogether—or perhaps they never really understood how.

“When women talk about gender [today], men feel attacked,” Evans says. “When black people try to talk about race, white people feel attacked, or they feel guilty. We never sit down and ask each other questions: How do you feel, why do you feel that way, why was that your reaction?”

Today, when Evans teaches on the topic at Georgia Tech, she makes her students anonymously write down questions they wish they could ask a member of another race, and then she reads them all out loud to the class. She says that the exercise is not about how shocking the white students’ questions are, “it’s how shocking everybody’s questions are.”

How come they can say the n-word and I can’t?

How come white people say ‘hello, how are you?’ and don’t actually want to know the answer?

Why are Asians such bad drivers?

How come white people wear shorts and flip-flops when it’s 30 degrees out?

“The total absurdity of the questions shows you how little we understand about each other,” Evans says. “And how we’re not willing to venture out because we can’t ask those questions.”

Evans’ point isn’t that anyone is “bad” for wondering these things, just as she isn’t trying to shame me when she suggests I take the Harvard Implicit Association Test. But while Evans’ early days in government may have been spent protecting against the glaring biases of Jim Crow and the open discrimination against women in male-dominated industries, in the 21st century she has focused on a subtler foe.

The antidote? We need to notice other individuals in their entirety, rather than shy away from what could feel “wrong” to acknowledge that we see.

We want to say, ‘When I’m hiring, gender and race doesn’t make any difference to me, I don’t even see it. All I see are the qualifications on the paper,’” Evans said. “It’s not true. And it doesn’t mean the person is bad, it just means the person somehow doesn’t understand.

I actually want people to be really aware of a woman,” Evans said. “And most black people and most Asian people and most Hispanic people want you to be aware: That’s who I am. That’s a good thing. That’s not something you deny.”