Behind the Struggle to Free South Africa

International civil rights lawyer Gay Johnson McDougall ’69 and the story behind what it took to free South Africa from apartheid rule. By Jeva Lange ’15

To dance the toyi-toyi you need to lift your legs high. You rock your body back and forth, as if you’re jogging in place to create a beat with your fellow dancers’ bodies, a pulse with your synchronized movements. And when your leader calls out ‘Amandla!’ or ‘power,’ you complete it with ‘Awethu!’—‘to us.’

“It’s sort of a dance and a jump,” Gay Johnson McDougall ’69 recalled of doing the toyi-toyi with the leaders of South Africa’s anti-apartheid liberation movement. “I was never able to master it. But it was the dance of activism that they’d do, and it was powerful.”

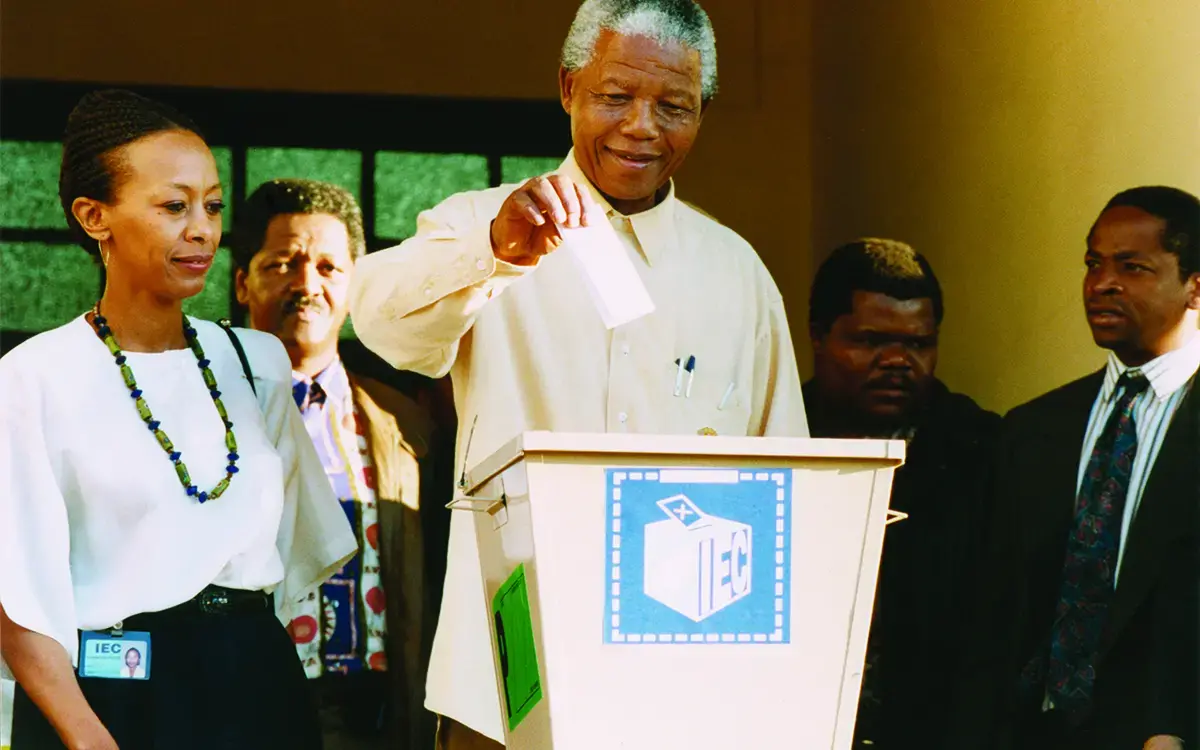

McDougall’s work is as powerful as the country’s protest dance. Early in her career she did what few thought was possible: mount a legal strategy and defense to help free South Africa from apartheid rule. If a picture speaks a thousand words, the famed shot of Mandela casting his ballot in the country’s first free election may speak to how central she was in the fight for freedom: she was right beside him.

Despite living and working across continents, McDougall’s early encounters with activism were not so unlike the stories of South African activists. As a child growing up in Georgia during the waning days of Jim Crow, McDougall was surrounded by homegrown resistance to American segregation. Her sister was active in the sit-ins in North Carolina. One of McDougall’s aunts worked for the YWCA, which attempted to unite white and black women across the South. McDougall’s great-grandfather was an influential AME minister and a presiding elder. And McDougall integrated Agnes Scott College, where she spent the first two years of her undergraduate education. Although, the integration only went so far. McDougall still remembers her meeting with the college’s president before moving in when she was told she’d be given her own room rather than be assigned the customary roommate, because the school couldn’t spring that on a white girl. “You understand,” he said.

She transferred to Bennington two years later, pursuing studies that would help her fulfill her dream of becoming a civil rights lawyer. Though, by the time she graduated the “air sort of went out of the movement.” It was an opening for McDougall and others with activists’ fire still in them to take up work through the Black Power movement to support African activists and their struggle for liberation.

Working for a national association of black activist lawyers McDougall was focused on linking the South African liberation movement to the civil rights movement in the U.S. In London, where she moved to continue her studies in international human rights, she quickly connected with the South African liberation movement’s arm headquartered there. “I was getting deeper into the fold,” McDougall laughs.

In 1980 McDougall moved back to Washington, D.C. to head the Southern Africa Project. “A lot was happening,” McDougall recalled.

The first couple of months after I moved to Washington when I would speak about apartheid, nobody knew what I was talking about, nobody cared. By the end of that year, the townships were being burned, people were rioting in the streets of South Africa. Everybody cared.

It didn’t take long for McDougall to go from being “a voice in the dark” to a voice of the movement and preeminent authority on South Africa. Her authority wasn’t just a legal authority, she was also becoming a fundraising force. She raised millions of dollars for the cause from donors throughout the world. The trouble was finding a way to smuggle those dollars into South Africa. “I tried to get into the country for years,” McDougall explained.

Despite years of trying, she was repeatedly denied visas to visit and she was never given a specific explanation as to why, but it was clear: her work was causing a lot of trouble for the white government. So her first visit to South Africa was one she made illegally in the mid-1980s when she crossed the Botswanan border in the trunk of a car.

On another trip, McDougall wanted to test if she could travel to Namibia on a Namibian visa, as the country was in the very early stages of being liberated from South Africa. But McDougall’s plane from Zimbabwe had to pass through Johannesburg, where the trip to Namibia was treated as a domestic transfer. “It was like flying from Georgia to Alabama,” McDougall explains. When her plane landed at the airport, a policeman escorted her to the Namibia departure gate. But, the plane to Namibia wasn’t scheduled to depart until the next morning.

“I had to stay in the airport all night, and the policeman said he had been instructed to stay overnight with me the entire time,” McDougall says. “The next morning he said, ‘You know, they told me that I should not leave you until you are strapped into the seat.’ Then he looked at me and asked, ‘Lady, what have you done?’”

Raising money, designing defenses from afar, where it was legal and safer, had certain strategic advantages but in struggles that call on such personal sacrifice and connections, being removed from her friends in South Africa was trying. “When people would get out of jail in South Africa and they would have a party, I was not there. When things went wrong…I was not there.”

It was particularly difficult when the African National Congress decided to use the defense strategy McDougall developed. A defense that had members go before the judge and testify that they were, in fact, prisoners of war and did not recognize the jurisdiction of the courts in South Africa. “Well, those first cases, the judge said, ‘Well okay, take them straight to jail.’ They executed them immediately. That was harder than missing the parties,” McDougall recalls.

In 1990, she was finally granted a visit visa to the country whose freedom she had long fought for. When she arrived, she found her name and work were well known to those in government and those on the ground. When McDougall presented her passport to the South African immigration officer he exclaimed, “You’re Ms. McDougall? Your file is gigantic!”

It was not long before the American lawyer with the gigantic file would be appointed to the Independent Electoral Commission, an international body of 16 members—McDougall the only American among them—designed to ensure that the first all-race election in South Africa was free and fair. It was a monumental call that required she move to South Africa during the year leading up to the historic event. “We decided everything about the election. How it would be conducted, where the polling stations would be, training people to be poll officers—the whole thing.”

Even with a year to prepare an election of such magnitude, nothing was taken for granted. She worked feverishly, around the clock putting out fires, including getting ballots to key townships where they were missing. In the famous photograph, where McDougall is pictured beside Mandela, she laughs out loud describing herself. “I’m comatose,” McDougall revealed.

After the election, McDougall returned to the U.S. with mixed emotions. It was in those first uncertain weeks that McDougall went with a friend to the house of the poet Maya Angelou, where she confessed, “I’ve already had the most incredible thing happen to me in my life.”

Angelou looked her in the eye. “Baby,” she said. “Don’t you dare say that. Because you never know what is coming down those lines.”

Angelou was right. Working to free South Africa from apartheid was only the start of what McDougall would contribute to advancing human rights around the world. She would be recognized by the MacArthur Foundation in 1999, honored with the prestigious “Genius” grant. She would become an independent expert for the United Nations’ International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and the first independent expert for the United Nations on Minority Issues. McDougall would become the executive director of Global Rights, Partners for Justice and work throughout the world, advocating and setting legal standards for the prosecution of systematic rape and sexual slavery during armed conflicts, and for equal opportunities in more countries that she can count off hand.

It is harrowing, unimaginable work. But, she told Law Crossing, “I can’t imagine that I could have had a more exciting and satisfying career. This has taken me right to the frontlines of a lot of human dramas. I’ve learned that there is a lot of suffering in the world, but right there is where you find all of the people who have an amazing wherewithal to overcome suffering, so you walk away with a net gain, in terms of inspiration and hope.”