Theaster Gates in Residence

The artist, curator, urbanist, and facilitator Theaster Gates was in residence at Bennington College in April, speaking to students, faculty, and staff about making place and making change, the two driving forces of his work. The highlight of his time on campus was the Adams–Tillim Lecture, which he delivered on April 25. By Aruna D'Souza

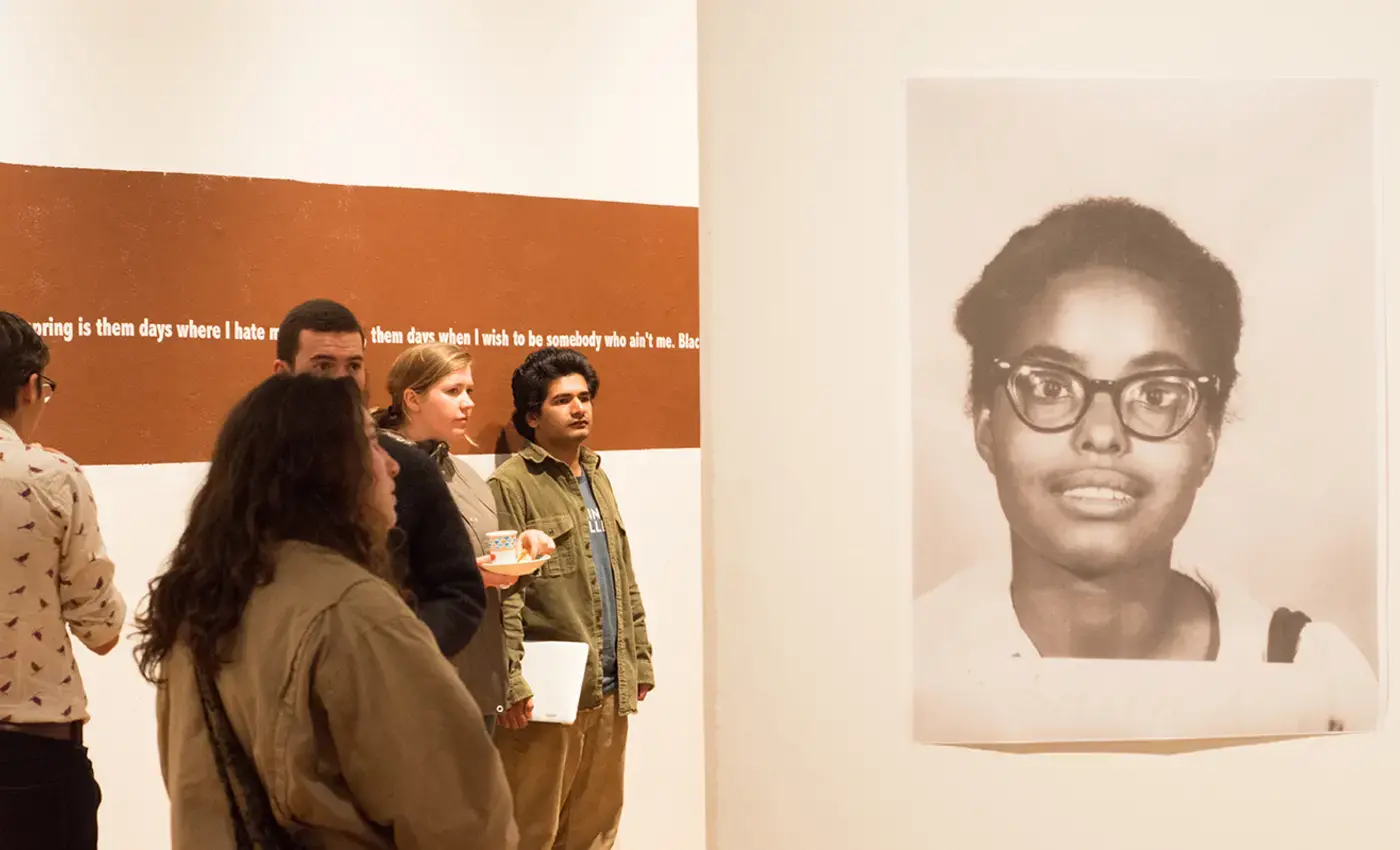

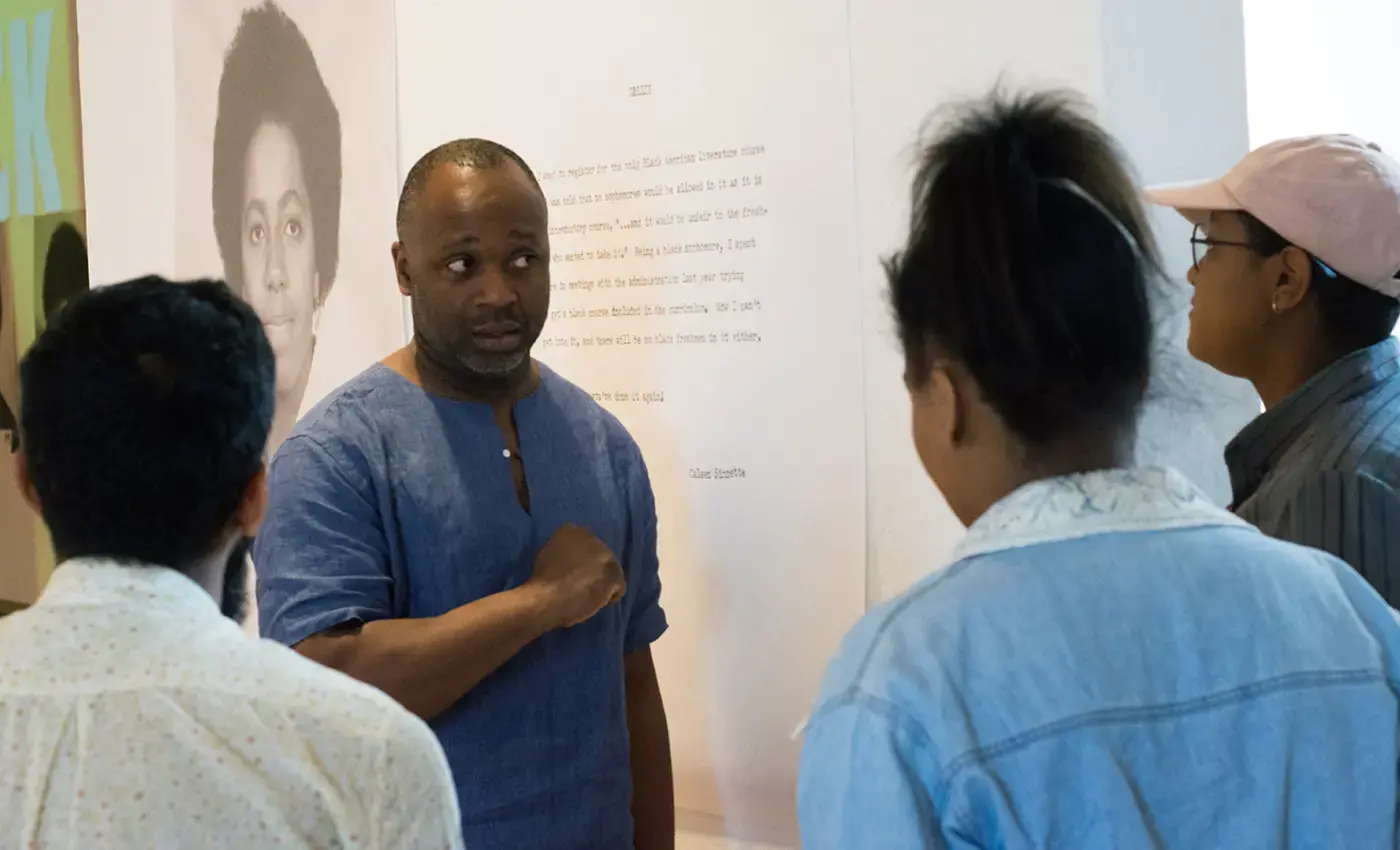

The invitation was prompted by a group of faculty and students who were interested in the history of the Black Music Division at Bennington College which was started in the early 1970s by faculty member Bill Dixon. Current faculty members Karthik Pandian (Video) and Michael Wimberly (Music) have been convening conversations with students, creating courses, and initiating projects such as Black Spring, an exhibition held in the Usdan Gallery from April 11–May 9 of this year, which explore the history of Black studies at Bennington and imagine what a program that reflected the issues of today might look like.

Gates, whose artistic career began as a ceramicist and quickly morphed into something that defies definition (“social practice” might be the closest description) is especially skilled at identifying potential that others overlook. His most well-known endeavor, the transformation of the neighborhood around South Dorchester Avenue in Chicago’s South Side, is a case in point: drawing upon, cultivating, and deploying the energy of the local residents, who had been largely abandoned by their city government, businesses, and investors, Gates developed the project through a series of canny real estate maneuvers, philanthropic investment, and long-term social engagement, financed in large part by the sale of his artworks.

It is a practice premised, writes the New York Times in a recent profile, on investing “in people and places others have written off.”

Working with the Rebuild Foundation, which he founded in 2009, and with the cooperation of Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Gates has amassed a staff of over sixty local residents to transform abandoned buildings into low-income housing. The staff members are gaining skills in demolition, construction, and masonry, which will, Gates hopes, offer them future employment opportunities for construction projects planned for the area, such as that of the Barack Obama Presidential Library.

In his telling, his practice is the result of a determination to harness the relatively limited resources available to him as an artist and private citizen, resulting in what he hopes will be large-scale social transformation.

On the strength of such work, Gates has been the recipient of a number of awards and honors, and his work is currently the subject of a solo exhibition—”The Minor Arts”—at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., until September 4.

Gates took part in a “Soul Talk” with Pandian, Wimberly, and current students Ash Haywood ’18 and Deja Haley ’20 in Usdan Gallery on April 25. Among an audience of around forty people, including a number of senior staff members, and against the backdrop of a faculty- and student-organized exhibition, “Black Spring,” picturing the past, present, and future of black lives at Bennington, Gates reflected on the role of race in institution-building.

He described Bennington as a place that had a lot in common with Black Mountain College—the storied incubator of some of the most important developments in mid-20th century avant-garde culture in the US—as “a platform where things might happen.”

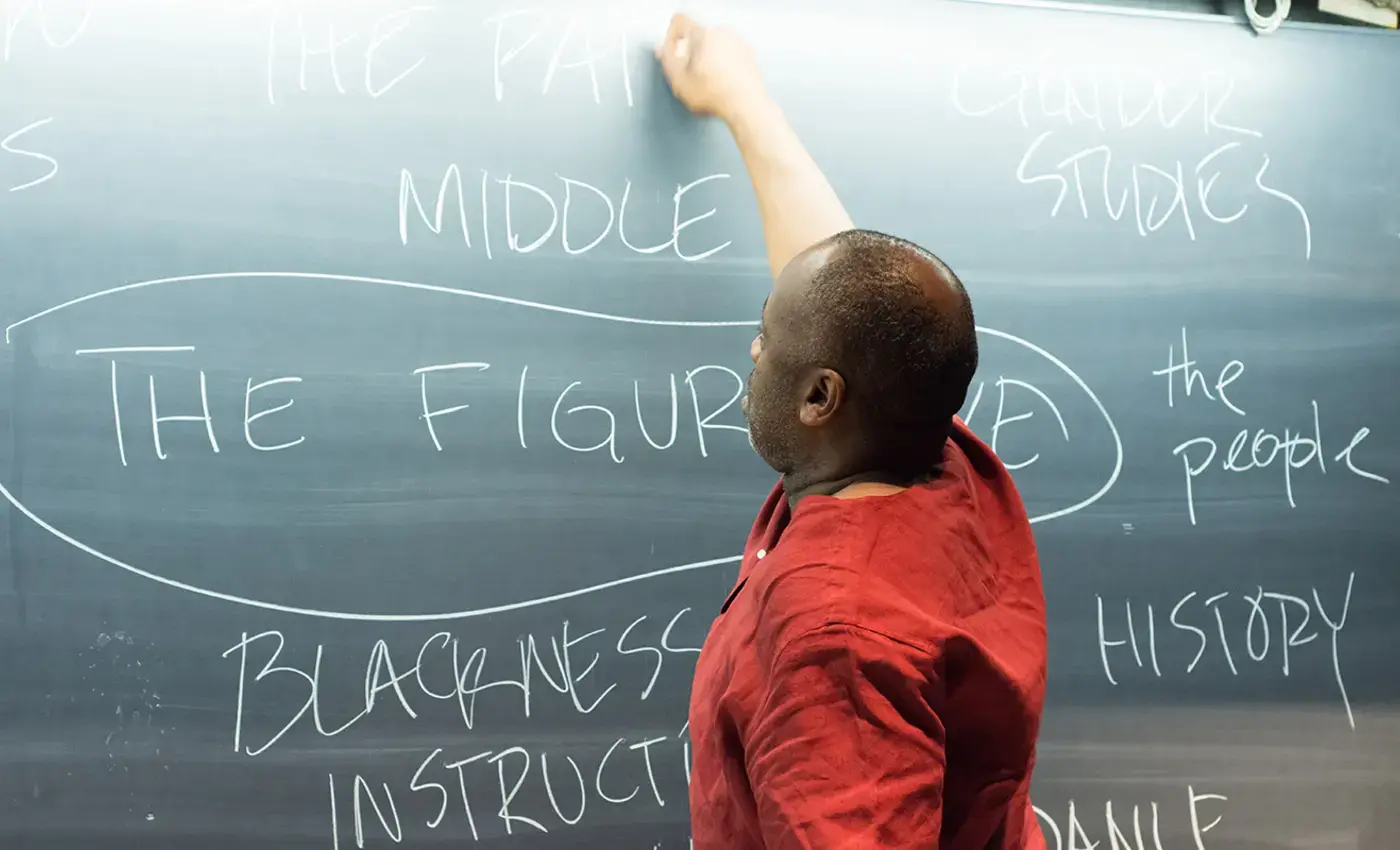

Given the spaces and resources available to students at Bennington—”You guys can use these buildings all night long!” he marveled—the vision for a new approach to thinking about the role of race in the arts, humanities, and sciences could in fact precede and determine how such a program would be administered. Along with the panelists, he discussed the tactical and practical possibilities of imagining a Black studies program, and the need to undertake solidarity and coalition building.

During the Adams–Tillim Lecture on the evening of April 25, Gates spoke further about his own work and the unexpected directions his career has taken. “The challenge is not that things aren’t possible,” he explained, “but that we don’t yet know the way.”

His work on the Stony Island Arts Bank—the transformation of an abandoned bank building into what is less a community center than an incubator of community engagement—began in response to teaching at the University of Chicago. (He currently serves as the director of the Arts and Public Life Initiative there.)

Finding that he couldn’t simply do the community work he wanted to do in the neighborhoods just beyond U of C’s gates, he devised a strategy of “mirroring” the things he was doing inside the university, outside it. “If I taught a studio course to tuition-paying students at the university, I would teach the same course for free to kids from the hood,” he explained. He began to show films at his apartment under the auspice “Black Cinema House,” only later moving the operation to the bank building.

The Stony Island Arts Bank opened in 2015 and attracted 60,000 visitors in its first year.

It became clear from Gates’ lecture—which, in truth, was as much a performance as anything—that his work has hinged on his almost unfathomable charisma (a quality that has been noted by almost everyone who has met him, and which he readily admits) as well as his ability to master, and even parody, the language of philanthropy and cultural revitalization.

He has no problem leveraging what he calls the art world’s desire for “proximity to charisma” in order to further his goals: “Can my presence as a cultural presence encourage other services to enter the neighborhood?” he asked at the beginning of his work on the South Side neighborhood. So far, the answer has been yes.

On April 26, Gates answered questions from students in a session titled “Art + Action” at the CAPA Symposium, hosted by faculty members Susie Ibarra (Music and CAPA) and Pandian. One of the questions he faced—and one that has been raised repeatedly in recent years in relation to his work—is that of gentrification: is the work that he is doing to revitalize the South Side of Chicago going to result in its historically black population being displaced by new middle-class white apartment-seekers, lured by the cultural cachet that Gates’s presence confers?

Gates’ response to this and other questions about the Dorchester project demonstrated his intricate knowledge of tax codes, real estate financing, banking mechanisms, and ownership structures in historically black neighborhoods. He is famous for having put all the money he has made from selling artwork—$17 million so far, he claims—back into community development, buying abandoned buildings in the neighborhood to retain black ownership in the face of predatory acquisitions by multinational banks.

When asked about the success of his efforts in Dorchester, Gates was reflective—and disarmingly forthright. “It’s working today,” he said. Whether it works tomorrow, he explained, with depend on whether he is able to take his ego out of the project and fully transform it into a community-driven endeavor. “It will happen,” he demurred with a smile. “I’m not quite there yet, but it will happen.”