Future Studio

By Aruna D'Souza

When faculty members Robert Ransick and Andrew Cencini launched Future Studio in the fall of 2014, they envisioned a class that would function as a startup. Students would work collaboratively to bring a product to market, taking on all the complexities that it entailed: research and development, prototype design, market and financial analysis, business planning, and potential public launch.

But unlike a typical tech startup, designed to maximize investors’ profit in as short a time as possible, Future Studio wanted to operate differently. How to calculate a financial return on an investment that took into account the well-being of workers, the local community, the environment, and social justice, too?

Ransick, whose work as an artist uses digital technology to spur public participation outside traditional spaces like galleries and museums, was curious whether imagining business as a form of art practice was one solution to this question.

He was so curious, in fact, that in the wake of the 2008 financial collapse and the Occupy Wall Street protests, while a full-time faculty member at Bennington, he pursued an MBA at Bard as part of his research. “The goal wasn’t simply to get another credential,” says Ransick. “It was to take a deep dive into the world of business in order to find out how the United States had gotten ourselves into the mess we had.”

The idea of Future Studio emerged as Ransick’s MBA capstone project.

“The business world always grabs from the artistic world in terms of creative strategies and has usurped a lot of language from art and design in the name of innovation,” he says. “What if we flipped those terms? What if we ran a business like an art studio, as a creative space where you can be creative and get things done and take it back into the world with a different set of values?”

So Ransick and Cencini—a computer scientist—assembled a group of students who came from all over the College, including art and design, technology, and The Center for the Advancement for Public Action, to undertake the two-term-long experiment.

In the first term, students focused on creative problem solving, design training, gaining business acumen, and researching alternative business models. The students organized themselves into four teams to develop product ideas, and by December presented their proposals to community members from the College and town. In the spring, they homed in on one product idea to focus their work, regrouping into teams oriented around engineering, design, business planning, and market analysis in order to test the viability of moving the project closer to market.

During the process, they consulted with advisors: local business leaders; representatives from organizations including the Small Business Association of Vermont, the Bennington County Industrial Corporation, and the Eastern Conference for Workplace Democracy; and alums including David Zicarelli '83, owner of Cycling 74, a software development company and music label specializing in interactive media.

Rohail Altaf '17, one of the two programmers in the class, arrived at Bennington from his home country of Pakistan with 12 years of tech experience under his belt. He has been coding since he was nine and received his first paycheck for building a website at 12.

“Just knowing how to program isn’t enough for me, though—I don’t want a cubicle job for the rest of my life,” he says about his decision to attend Bennington. “Future Studio was the perfect opportunity for me to expand my tech knowledge and apply it in a broader sense—to take a skill set I have and to collaborate with other people with completely different skill sets to craft a product and create a team.”

Sarah Shames ’17 came into Future Studio with some skepticism—“I’m from Palo Alto: anything that was calling itself a startup was a bit off-putting to me”—but took the course at the urging of her advisor.

She knew she would have something to contribute: in her first year she had done her Field Work Term at the Small Planet Institute, teaching herself how to use a number of design software programs on the job. That experience would end up being invaluable when it came to product development. Little did she know that she would also end up drawing upon her CAPA training in conflict resolution, or moving into completely foreign territory, by developing a business plan.

If she started out worried that she was in for the typical Silicon Valley experience, that disappeared quickly: from the moment she stepped into the classroom, it became clear that this wasn’t going to be your average startup—or your average course.

For one thing, Ransick and Cencini conceived the class as a true collaboration, and their roles as that of co-founders rather than traditional faculty members. “There was a lot of discussion about how they should approach conversations and what the students needed from them,” says Altaf. “We could say, ‘You’re acting like teachers right now and we need you to act like co-founders.’ But sometimes when we were completely lost, we did need them to act as teachers, give us resources, guide us further, and they did that, too.”

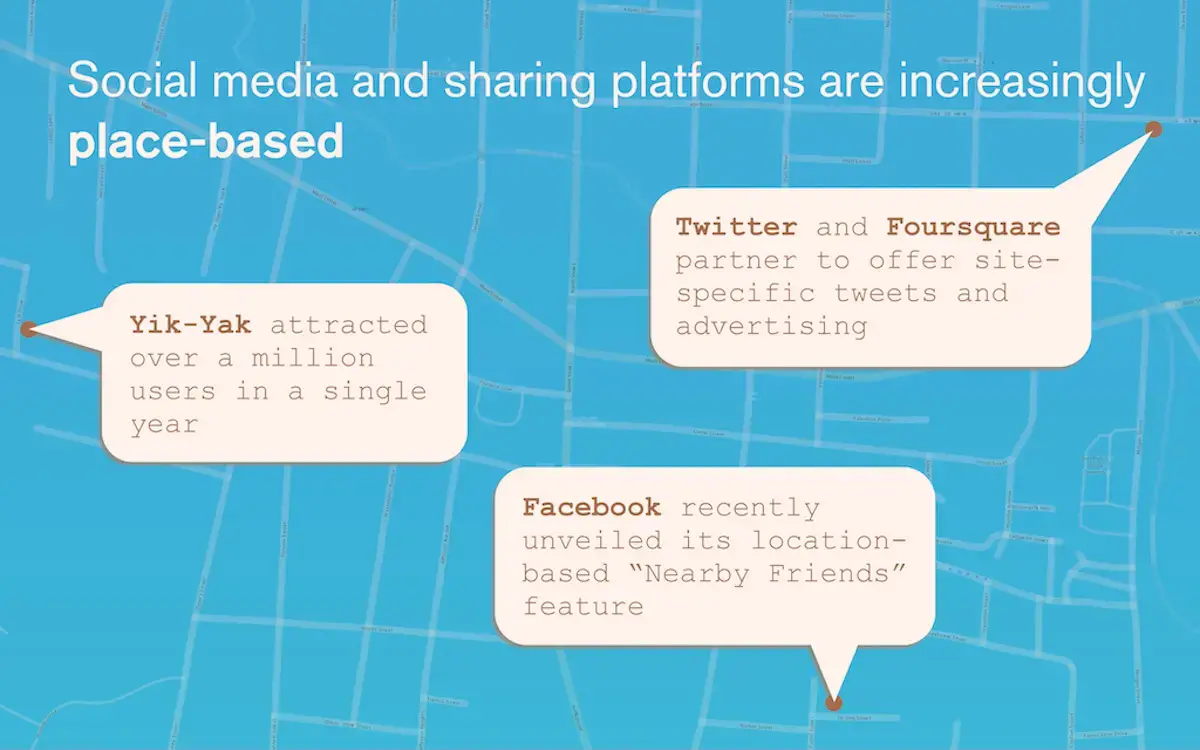

For another, the students became literal stakeholders in the activities of the class: if and when the prototype that they worked on during the year—Chestnut, a location-specific, beacon-based technology that allows people to share messages and creative work in the form of video, music, text, GIFs, and images—is further developed and brought to market, everyone who participated in the process will receive some equity in the company.

Just knowing how to program isn’t enough for me, though—I don’t want a cubicle job for the rest of my life.

The course ended in June, and a core group of students are working with Ransick on the next stages in the process of making Chestnut a reality, which includes extensive revisions, business development, user testing, and the search for financial backers who fall outside the traditional Silicon Valley venture capitalist model and can embrace the long-term goals of the undertaking.

For Ransick, Bennington has been the perfect place for such a pedagogical experiment. The students are ready for the challenge, he says, in part because they’ve been primed for it by the Plan process.

“I believe the Plan experience is the biggest gift that Bennington gives students,” he says. “When they leave here, when something unexpected happens in their lives or when an unforeseen opportunity emerges, they aren’t paralyzed— they instinctively know what to do. They ask: what are my interests and what direction do I want to be heading, who do I talk to to find out how to do it, what are the resources I can draw upon? They do the research to figure it out, keep iterating on the idea in order to move forward. That’s a lot like being an artist and it’s a lot like starting a business—there is no pre-defined road map or set of instructions. And that’s what Future Studio hopes to be, too.”