A Digital Union

To remain relevant and agile, worker organizations must embrace the opportunities the digital landscape brings. From top down to ground up, by Jess Kutch '03

Last summer, something extraordinary happened. Thousands of employees of the New England grocery store chain Market Basket initiated a weeks-long strike and customer boycott across 71 stores.

These striking cashiers, deli clerks, and bakery managers didn’t belong to a union. They had no professional organizers or labor groups helping them, either. Instead, these workers used the tools available to them—Facebook, Twitter, and a GoFundMe page that raised nearly $100,000 for a strike fund. As the strike swelled in July, more than 90,000 people followed an employee-run Facebook page to stay informed of upcoming rallies and strike actions. The #savemarketbasket hashtag frequently trended on Twitter, and employees used the @moreforURdollar Twitter account to respond to numerous media requests.

The purpose of the strike was to stop the ousting of a beloved CEO—Artie T. Demoulas—by a hostile Board of Directors. Under Demoulas’ leadership, Market Basket had implemented a profit-sharing program, employee scholarships, and wages that were at least four dollars per hour above Massachusetts’ minimum wage. With the firing of their CEO, employees predicted that cuts to their wages and benefits were not far behind.

By the end of the summer, the company was so crippled by the strike and boycott—losing an estimated $10 million each day—that the Board relented and allowed Demoulas to return to the company. The workers had won.

The Market Basket story may seem unusual, but it’s also an indication of what’s to come.

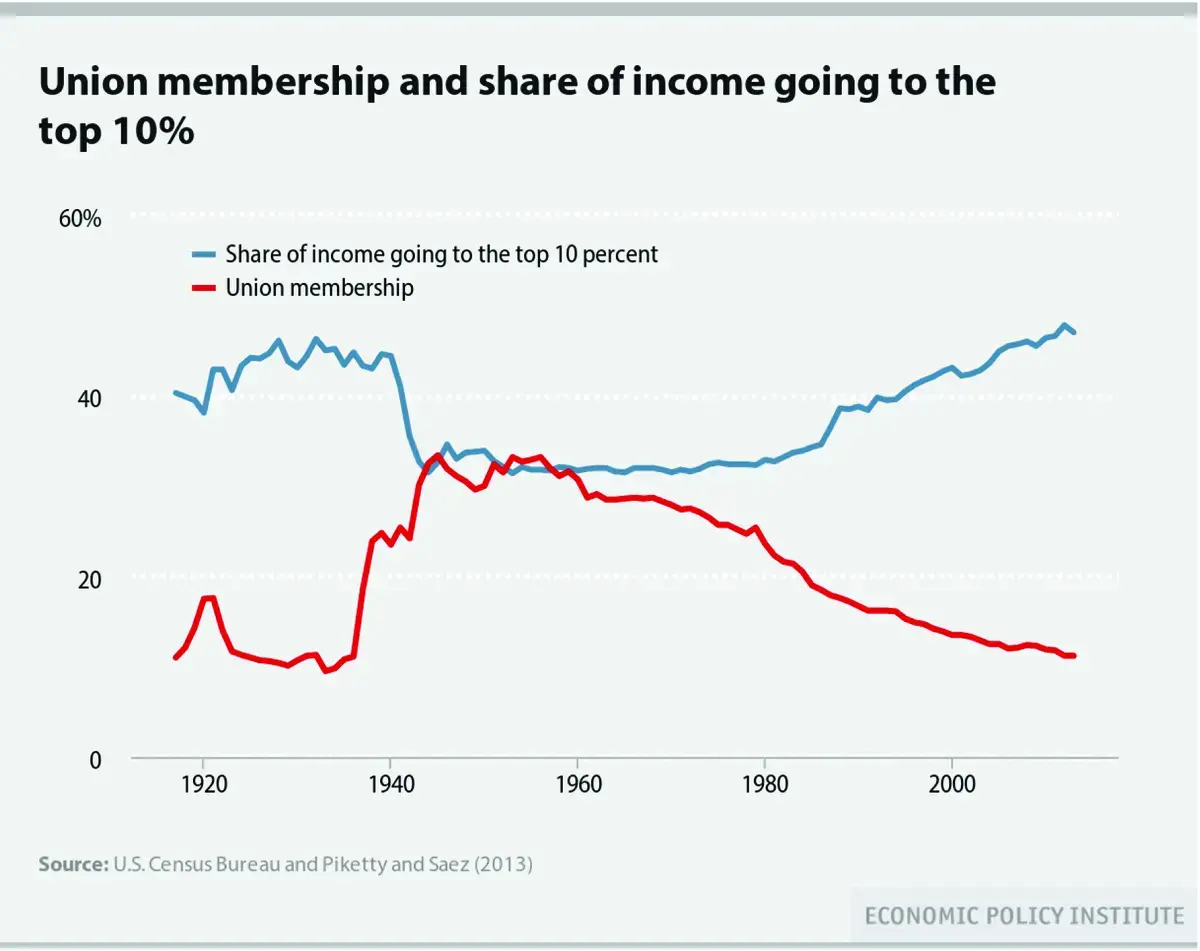

Regardless of what you think about the labor movement, you can’t deny its impact in raising the wages and benefits of both union and non-union workers in America. Through sit-down strikes and picket lines, union members managed to win higher wages and benefits like retirement security and health care. Today, union members are 60 percent more likely to have a pension and earn roughly $200 more each week than their non-union counterparts. But in the past 30 years, union membership has plummeted and wealth inequality has risen sharply. While many factors have contributed to these changes, data suggests there is a strong correlation between de-unionization and rising income inequality. The chart on this page shows the mirror-like relationship between these two trends—as union membership climbs, the top 10 percent of earners take home a smaller share of income. Today, private sector unionization is hovering at just 6.6 percent, and the top 10 percent of earners are now taking home nearly half of all income.

The Market Basket story may seem unusual, but it’s also an indication of what’s to come

For the past few decades, many labor leaders tried to stop this decline. The AFL-CIO shifted resources toward new organizing and political lobbying, and some unions merged to consolidate membership. But none of these experiments stopped the year-over-year decline in union membership rates. There are numerous reasons for this (for example, increasingly sophisticated union busting, “right to work” laws, etc.), but one thing is clear—the brick-and-mortar trade union of an industrial America is a poor fit for the increasingly fluid, fast-changing workforce of the 21st century. And as technology makes it easier for people like the employees at Market Basket to share information, make decisions, and take collective action, the top-down, opaque structures of labor unions will appear increasingly outdated.

If unions are no longer viable for the vast majority of workers, we must create the conditions for new solutions to emerge. The question then, is how?

The modern U.S. labor movement was born in the chaotic final decades of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Industrialization had dramatically altered life in American towns and cities. For labor organizations, one of the most significant changes was the shift away from regional craft employers toward large-scale, national corporations (or “trusts”) like U.S. Steel. Several labor organizations emerged to confront this new reality—the National Labor Union, The Knights of Labor, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and later, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). These organizations experimented with worker cooperatives, mutual aid programs, political lobbying, and alternative revenue streams in an attempt to scale up their presence. Some organizations found enormous success—though many wouldn’t survive. At one point, the now-defunct Knights of Labor claimed one-fifth of all U.S. workers as members. In post-Civil War America, every labor organization was a start-up. And every union organizer, a social entrepreneur.

One thing is clear—the brick-and-mortar trade union of an industrial America is a poor fit for the increasingly fluid, fast-changing workforce of the 21st century

We’re in the midst of a similar transformation for 21st-century workers. The economic changes of the Information Age will be as cataclysmic as the Industrial Revolution. Entrepreneur Micha Kaufman argues, “The Internet Revolution is in fact the Industrial Revolution of our time.” If this is true, the models that served us for the past 100 years—on the factory floor and in the office tower—no longer meet our rapidly evolving needs. Even the language we use to describe work is going extinct. Harvard business professor Shoshanna Zuboff recognized this all the way back in 1982, when she noted in her seminal work In the Age of the Smart Machine that our language surrounding work “is still one of a manufacturing enterprise where raw materials are transformed by physical labor and machine power into finished goods.” She concludes, “the images associated with physical labor can no longer guide our conception of work.”

But as these changes take hold, we are adapting. People are finding new ways to influence employers on the age-old issues of wages and working conditions.

Digital tools are enabling workers to advocate for themselves in ways that were previously only possible with the backing of a well-staffed union or law firm. In 2013, a Yemen-based freelance journalist, fed up with late payments, created the website “Pay Me Please” for freelancers to publicly report corporate clients with past due bills. Last year, a New York-based Uber driver created his own website (udriversnetwork.com) and built a network of drivers to push for better treatment from the platform. And on reddit.com, thousands of anonymous workers use employer “subreddits” to share information and safely in anonymous whistleblowing.

Today, union members are 60 percent more likely to have a pension and earn roughly $200 more each week than their non-union counterparts. But in the past 30 years, union membership has plummeted and wealth inequality has risen sharply

At Coworker.org—an organization I co-founded in 2013—we’re building the digital infrastructure to nurture and develop this nascent workplace activism. Our community of users includes American Airlines flight attendants, Uber drivers, Wells Fargo bank tellers, college faculty, and baristas. For example, more than 24,000 Starbucks baristas in 17 different countries—or, 8 percent of the Starbucks total global workforce—have used Coworker.org to win everything from scheduling improvements to changes in the dress code. Baristas in the Philippines are teaming up with their counterparts in Australia and Canada to challenge a multi-national employer. None of these advances came out of the traditional trade union model.

The economic changes of the Information Age will be as cataclysmic as the Industrial Revolution

For the first time in human history, workers can communicate and organize in real time, across great distances, and can speak directly to decision-makers in the C Suite. What we’re seeing on the internet right now are the seedlings of a future labor movement—one that is highly decentralized, global, and driven by technology. Labor unions as we’ve come to know them may be dying, but the labor movement is on the verge of another renaissance. From these tiny digital uprisings, a new model for worker power will emerge.

Jess Kutch ’03 is a digital strategist and co-founder of Coworker.org, an online platform for workers’ rights. Previously, she served as organizing director at Change.org, where she led a team of organizers in providing strategic support to campaigns on Change.org’s platform. Her work raised Change.org’s profile around the world and helped inspire thousands of people to launch and lead their own campaigns. Before joining Change.org, Jess spent five years directing online campaigns for the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). Her work has been profiled by top-tier media outlets, including ABC World News, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. She is a 2014 Echoing Green Fellow and a Senior Fellow at the New Organizing Institute.