Science in Seattle: Studying Fat in Fruit Flies

How does the fat distribution and aging process in fruit flies illuminate how the human body functions? Tom Evans ’24 dove into this question at a pathology research lab in the University of Washington (UW) during the Summer 2022 Field Work Term (FWT).

By Halley Le '25

Diving into opportunity

Tom Evans ’24 is a junior studying Biology under the guidance of faculty advisor Amie McClellan.

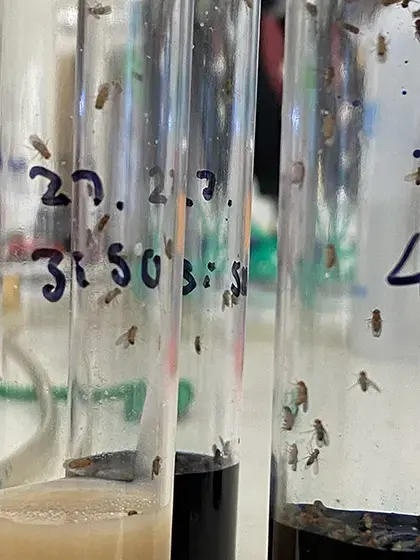

“Through email outreach, I found the opportunity to assist the Promislow lab at UW in a fruit fly pathology research project,” said Evans. The lab focuses on understanding aging in humans, and fruit flies are an ideal model organism for aging studies due to their low cost, rapid lifespan, and well-studied genes.

“The study I got involved with is based on sexual dimorphism and TAG levels, which indicates that the males and females of the same species can display distinctively different fat levels. This difference also varies across lines of the same species,” explained Evans. “By studying the fat distribution in multiple lines of fruit flies, we can understand why sexual dimorphism exists, or why females tend to accumulate more fat than males.”

When Evans arrived on UW campus, they were initially tasked with dissecting fruit flies and monitoring how the flies' fat changes and ages overtime. While hearing the explanation for the procedure, however, Evans suddenly thought of a detail that would alter the course of their research.

“I was curious if we know how much food the flies consume,” Evans recalled. “So I raised the question.”

To their surprise, no one had the answer.

“My logic was that, conventionally, the more food you eat, the more fat you will accumulate. This might seem intuitive for me as an outsider looking into the research,” remarked Evans. “But I think it is so easy to get engrossed by the big picture that even the most experienced researchers can overlook the more subtle details. Just like how advanced math students are sometimes confused by simple equations!”

Dr. Daniel Promislow, principal investigator (PI) of the study, senior scientist Ben Harrison and Ph.D. candidate Rene Coig, Evans’ project mentor, thought they raised an excellent inquiry. Instead of their original assignment, Evans was tasked with developing a lab specific protocol to measure how much fruit flies eat everyday.

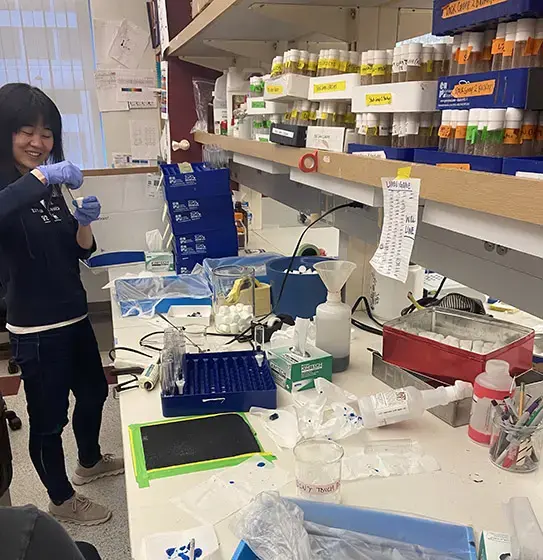

“I spent hours reading articles and comparing options and found the perfect tool – a dye that allowed me to turn the flies' food blue.” explained Evans. “The next step involves feeding flies the blue dyed food and leaving them for 24 hours in a vial so they excrete what they eat. Their excretion is blue and soluble, so we can dissolve it in water in addition to a homogenized fly sample to collect residual dye inside the fly, to indicate how much food the flies have eaten based on blue dye concentrations.”

While Evans based the experiment protocol off of similar studies, they added their own development to make the procedure compatible with their own goals and the equipment available in the lab.

“Conventional protocol only looks at the excretion,” said Evans. “However, after 24 hours, the flies wouldn’t have finished digesting all their food, so I had to find a way to take undigested food into account. I ended up having to crush up the flies, individually, to extract a gut sample and measure the food that is left in their guts.”

While Evans performed the blue dye protocol, Coig utilized another method to examine the fat content of the flies. Coig’s fat measurement data and Evans’ consumption and excretion data will be compared and analyzed using R and appropriate data analysis methods.

“My PI thought I had “intriguing” data. I found a somewhat linear relationship between food consumed and fat stored; however, the correlation was not significant enough to draw a conclusion,” said Evans. “There are a lot of variations within our experiment organisms: for example, Rene and I had to use different flies lines due to the flies’ aging span. Difference in genomes, lines, and sexes also create variety within the data.”

The study is ongoing, and Evans will return during the Winter FWT to improve upon the two protocols and eliminate the variations. They are currently designing a new protocol that will allow them to use the same line of flies to perform both measurements.

Exciting and Terrifying

Reflecting on what most excited them about their summer research experience, Evans had several memories.

“The lab mentors gave me complete freedom. This is my first real lab experience, so the freedom was exciting and terrifying! They even gave me the title of ‘visiting researcher,’ which made me feel appreciated,” said Evans. “Additionally, I am stepping into an unexplored path, because no one in the lab had conducted a version of this blue dye assay for many years.”

“I was in the lab almost every single day for the entire duration of the summer,” said Evans. “I spent some time just exploring and failing, but I also learned a lot and developed meaningful relationships with my lab cohorts, which gave me confidence in my own ability as a researcher.”

After Evans established their protocol, it was also shared with the larger scientific community. Another visiting researcher from India learned about Evans’ procedure and they discussed applying it at his lab in his home country.

“The experimental process itself was satisfying. The blue dye is extremely saturated and permanent, and the day I started my first trial with 4 liters of the dye, the whole lab was watching me to make sure none would spill on the floor,” said Evans. “I walked in Seattle covered in blue all summer, I have stories of how I feed hundreds of flies every day, and I left a blue stain on the lab floor that will never come out. Even if I didn’t have any impact on that lab, they will always remember me!”

Reframing education and the Bennington experience

Coming into and leaving the lab, Evans reflected upon their education. While their Bennington experience greatly helped prepare them for the summer research, the experience itself helped them reframe their Bennington education.

“As a FLoW international student, it can be more difficult to find summer research opportunities, because students on an F-1 visa are not eligible for most research programs, which are government-funded,” said Evans. “But Bennington taught me responsibility and self-advocacy, so I was not going to let these obstacles beat me.”

A friend had offered Evans housing in Seattle, so naturally, they looked into the University of Washington. They read up professors’ bio, articles, and ongoing research news, and emailed any professor that sparked their interest. Dr. Prosmilow responded, and two weeks later, Evans boarded their flight.

“I forged my own way, which was how I was brought up as a FLoW student,” said Evans. “Bennington’s Plan process, which asks us to justify all the classes we take and the projects we commit to, taught me the value of this self-advocacy.”

Evans’ experience at the University of Washington, in turn, helped them redefine themself and their trajectory of education.

“A thing I learned from my lab manager, a professional in the field of aging research, is that drive and motivation matters more than grades,” recalled Evans. “He had a 2-point-something GPA in college, and he is now leading his field. It is inspiring to see people pursuing science out of passion, not just because they got all A’s in school or felt pressured to do it.”

Previously, Evans’ Plan involved exploring the interdisciplinary relationship between art and science with a pre-med focus. Their latest research undertaking, however, made Evans realize they are interested more in scientific academic research. As Evans returns to campus, they will consolidate their Plan, as informed by their summer experience, to focus more on cellular biology and pathology.

Evans is now interested in the ways that research can be made more accessible to others without a strong STEM background. The ultimate application of their research this summer was to find possible genetic components to weight gain, which helps to destigmatize and demystify it.

Since this kind of research is applicable to a huge audience, Evans wants to make it so all people can understand the findings.

At Bennington, for Evans, this looks like presenting their findings in “unconventional” ways in order to overcome barriers and make findings more accessible and relevant to those the research affects.

“I am thankful for my mentors at UW for having confidence in me and for making my summer memorable,” said Evans. “I want to credit my family, my incredibly supportive friends, my advisor Amie as well as faculty members John Bullock and Blake Jones for pushing me to pursue this opportunity and giving me the knowledge and confidence to achieve what I at one time didn't think would be possible for me. I hope that every Bennington student understands that they have the ability to find something they are interested in and to advocate for it. Don’t be afraid to put yourself out there. My parents have told me for as long as I can remember that you don't get anything that you don't ask for, and I live by that. Figure out what it is you want, no matter how big or small, ask for it, acknowledging that you are worthy of it, you never know what might happen!”