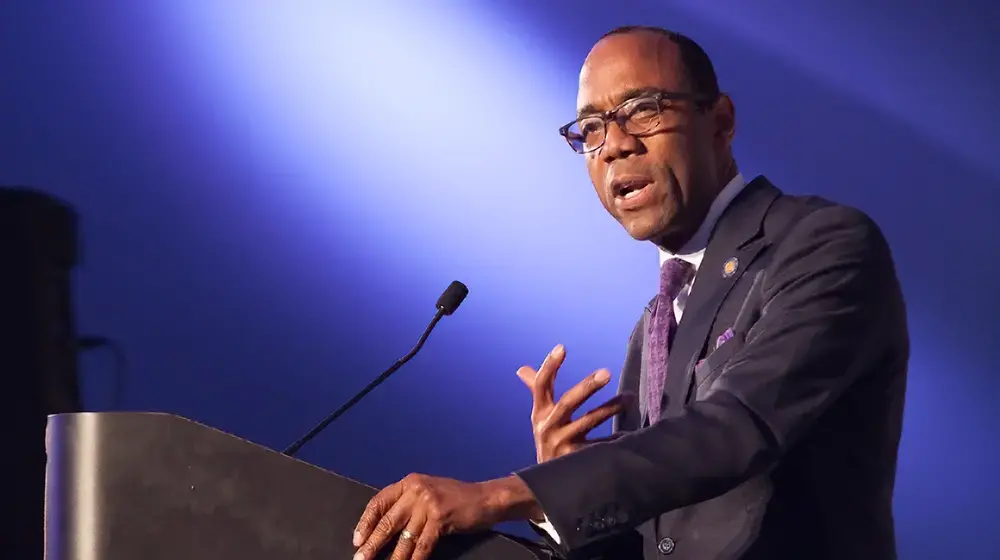

Cornell Brooks: "Love Boldly, Lead Bravely"

Cornell William Brooks, President and CEO of the NAACP, gave the Commencement address for the graduating class of 2017.

Good evening. [Audience: Good evening.] Now, if I were at Williams or Amherst, that "good evening" might suffice. But since I'm at Bennington College and this is commencement, I'm gonna say, "Good evening," again, and I wanna hear it like everybody here is extraordinarily ecstatic, okay? Good evening. [Audience: Good evening!] I know I'm at commencement.

My very Southern grandmother, Mrs Rosalie Prioleau, taught me by the eloquence of example, to begin every speech, every talk, every sermon, with these words, "Thank you." To the 2017 graduates of Bennington, I simply wanna say to you, "Thank you for allowing me to be a part of this commencement." Put your hands together for yourselves, for all you've accomplished, for all that you've done.

[dog barks] [laughter] President Silver, is he getting a degree?

President Silver, thank you for extending to me an invitation to be a part of an extraordinary moment in the lives of these graduates, in the life of this college. Thank you for, not only the invitation, but also for your leadership. Your leadership coincides with the Twitter age civil rights movement we find ourselves in. Your leadership coincides with the struggle of people of color. Your leadership coincides with the threats to this democracy, and your leadership on this campus is a representation, and is emblematic of that which should be done elsewhere. I'm gonna ask everyone here to put your hands together for your president.

President Silver, you spoke about being thankful that there was a meal separating my speech from your speech. Kat, there was no meal separating your speech from my speech. To an extraordinarily eloquent student commencement speaker, whose words were given effect and meaning by the organization, by the advocacy, by the deeds of dedication that preceded this speech. So for that, for all of the students who stood with you over the course of these years, for your comrades in this advocacy fight here at Bennington, I want you to put your hands together for the speaker, and for the organization, and for Bennington College, can you all do that?

To the graduates, I ask that you look to your left and to your right. I ask that you look forward and behind you. I want you to look across the length, and breadth, and the expanse of this audience, and if you see one mother, one father, one aunt, one uncle, one grandmother, one grandfather... If you see somebody who's loved you, if you see somebody who's believed in you, if you see somebody who's lifted you up, if you see somebody whose friendship and care you respect and you appreciate, I want you to put your hands together for your family and friends, loud, long, and resoundingly.

Graduates, one more small request. Look around this tent, and if you see a faculty member who's encouraged you, who's given you thoughtful comments on a paper, who's lifted you up...If you see a member of the staff who's maintained the grounds, prepared food for you...If you see someone whose service you're grateful for, you're appreciative of, I want you to put your hands together, loud, long and resoundingly, in deep appreciation for all that you've been given. Can you do that?

To these graduates, members of the faculty, the staff, the board of trustees, I need to let you know that as a fourth generation preacher and as a trial attorney, I'm not always been so fortunate to be in the midst of such a distinguished and august group of people.

In fact, I can think of a time many years ago, when I found myself as a student in London, England on a Sunday morning. I found myself as a student standing outside of this beautiful Gothic cathedral with spirals soaring up toward the heavens, stained glass windows reflecting the iridescent multi-hued, multi-colored beauty of God. As a young, innocent, naive, presumptuous preacher standing outside of this Gothic cathedral, I assumed that there were 2,000 or so folks waiting to hear this young, naive, presumptuous preacher preach.

Now, Kat this is a true story. Now, I made my way into the sanctuary and I immediately noticed the obvious, the pastor and exactly two members. One member I'll call Miss Smith, the other member I'll call Miss Jones. Now, I did as I was taught to do, which is to say that you speak, you share, you preach to two people in the same way that you would to 2,000, with sincerity, with conviction, with a sense of one's purpose and calling. I made my way into the pulpit, and I began to speak, and I immediately noticed the obvious, that Miss Jones immediately fell asleep.

True story. Now, this only inspired me to speak with greater conviction.

And as I was speaking, I immediately noticed the obvious, that Miss Smith seemed to hang onto every word I had to say. She nodded her head, she tapped her toes, she clapped her hands, she said "Amen" and "Hallelujah" at all the right theological and liturgical moments. I thought to myself, "At least I'm reaching one somebody this Sunday morning." While I concluded my sermon, made my way out of the pulpit, made my way to the side of the pastor, and the pastor said to me, "Brother Brooks, I'm just so sorry. Miss Jones falls asleep on everybody, and Miss Smith is out of her mind, and did not understand a thing you had to say."

True story. So you can see why I'm so delighted to be here at Bennington College, where everyone is wide awake, and presumably sober, and in your right minds...

This June eve, amidst this bucolic setting on this beautiful campus occurs at a particular and peculiar moment in American history. This commencement ceremony occurs at a moment in American history. It is an occasion for unapologetic celebration. It is a moment in which graduates can rightly commend themselves for the journey that they have made, a journey of mind, a journey of heart, a journey of aspiration. It is a moment to celebrate your friendships. It is a moment to celebrate the novel, the play, the exhibit, the person you fell in love with. It is a moment to celebrate a field work term, in which you discovered not merely work that you love, but the reason why your friends and your family love you and regard you as special. It is a moment to celebrate faculty members and staff who transcended position descriptions to embrace and love you as an intellectual, as a scholar, as a friend, as a budding professional. It is a moment to celebrate friendships that reaffirmed who you are, what you stand for, and who you can be. It is a moment to celebrate this great legacy of advocacy, and aspiration, and moral ambition that you are heir to.

It is a moment to celebrate how far you have come, the distance that you have traveled, the dreams that you've dreamed, the visions that you have envisioned, the work that you've completed, the person you have become. It is a moment to celebrate. But this moment occurs, not at some random moment on the Gregorian calendar. This is not some random Twitter moment. This is a peculiar and powerful moment in history. It is a moment in which, beyond this campus, and even on this campus, we have a generation of millennial activists, who've asserted with their minds, with their bodies, that black lives matter.

It is your generation that has asserted before the country, that black lives matter, understanding profoundly, that black lives matter is the moral predicate to the ethical conclusion, that all lives matter; unless the first is true, the second can never be true.

It is a moment in which a generation of millennial activists, from Ferguson to Flint, have literally put their bodies on the line. It is a moment in American history in which our nation has endured a presidential election, in which we have seen racism routinized, anti-Semitism normalized, we've seen Islamophobia de-exceptionalized, members of the LGBT community otherized, and misogyny mainstreamed. It is a moment in which your generation has asserted loudly and clearly, "No, we will not descend into this otherization of America. No, we will not give over our dignity. No, we will not give over our rights. Yes, we will resist!"

There are many, who on this occasion, attempted to despair, attempted to grow weary in well-doing, to grow cynical about the capacity to effect change, but I want to draw a few lessons from my experience over the course of the last few years, which coincides with the tenure of your president and with your years here at Bennington. If I could just draw a few lessons from a movement, a few life lessons from a movement, those lessons might be characterized quite simply. Number one, look for role models, but not too hard. Look for role models, but don't look too hard or too far away. Second, I wanna suggest to you that we love boldly. Love boldly, not timidly, not with fear or apprehension, but love boldly. And lastly, I wanna suggest to you that we lead bravely.

Over the course of the last three years, during my time as President and CEO of the NAACP, I met a great number of people who have tried to convince me to engage in hand-wringing despair. But I'm reminded that when you read the history of social movements, when you read moral philosophy, when you read and understand the theology of the Hebrew prophets, you understand that hope is not an emotional luxury, it is an existential necessity. You understand that hope, it is that which allows us to envision a world that we can yet create. We understand that hope is paint, and pixels, color, texture, shadow, and shade of a moral imagination, that can literally create a world. We're reminded that the prophet Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel said that, "Words are worlds." We can speak that which we aspire to into existence. Words to our friends, words to our country, words to our nation, words to the world, we can speak and act, and through the eloquence of example bring into being that which we deserve.

And so, I'm not tempted to despair, and so I want to just suggest to you this evening that we look for role models, but not too far. In the course of my travels, from Charleston, after nine students of the scripture were slain in a church, to Michael Brown's Ferguson, or Freddie Gray's Baltimore, or Tamir Rice's Cleveland, over, and over, and over again, I've seen role models. These role models have not been graced with gray hair and long years. These role models are not tenured members of distinguished faculties. These role models are 18 years old, 19 years old, and 17 years old. When I got off a plane in Minneapolis, Minnesota, after the death of Jamar Clark, and went into downtown Minneapolis, and stood with high school students and college students in the middle of the night, as they lit bonfires in 20 degree Minnesota weather, protesting injustice. The next night, I spoke at a rally. A few hours later I left, flew back to our headquarters in Baltimore. Two white nationalists went to the same street corner I stood on, shot five people with bullets of racial animus, bullets of bigotry, bullets of despair, bullets of cynicism. But can I tell you, my high school role models, my college role models did not give up. They did not give in. They did not give over. I admire them!

When you see students carrying books of poetry, books of Shakespeare, books of engineering, books of chemistry, but also books of advocacy, books of love, books of justice, and they're reading from those books and translating those words, into deeds and into action, you have to admire them. But may I suggest to you that my role models are not only the generation before us, but I wanna suggest to you that my role models are also in the generation that precede us. My granddaddy, the Reverend James Edmund Prioleau, was a preacher and also a barber. As a little boy, my grandmother would send me down to his barbershop to get my hair cut, not because he was a particularly stylish barber, he was free.

As I sat in the barber chair, my granddaddy would tell me stories about advocacy, stories from his youth, and I didn't believe him. I doubted him. I thought that these were tall tales of an old man. Many years later, as a student, my friends were passing around a book of photographs, and I flipped through that book of photographs, and came across the picture, a sepia-toned picture of yesteryear, a black and white photograph of a time gone by, and in that picture was a young man by the name of the Reverend James Edmund Prioleau, candidate for congress in 1946. He ran for congress after Thurgood Marshall won a case called Smith vs Allwright, which outlawed the all white Southern Democratic Primary, which kept blacks out of the ballot box and on the periphery of our democracy. My granddaddy ran for congress, ran against the Klan, ran against racial animus, ran on behalf of a cause greater than himself. He didn't run because Fox News told him he was a viable candidate. He didn't run because the polls told him he could win. He ran because he believed in his people and he believed in the cause of justice. I admire him!

Tonight, I need you to look for role models. These role models may not be on television. These role models may not be on your Twitter feed. These role models may not be on Snapchat. These role models may live in your house. They may be called Mama and Daddy. They may be called aunts and uncles. They may be called Grandma and Grandpa. The role models that you need are right around you, you need not look far.

To these 2017 graduates, I ask that you not make this mistake I made. It took me years. It took me the time between being an elementary school student and a student at Yale Law School to appreciate what my grandfather did, to appreciate his sacrifice, to appreciate his love, and his faith, and his affection for his people. I ask that you believe in the role models that live in your house, the role models that sent you to Bennington, the role models that are seated here tonight. Believe in them, love them, care for them, respect them, put your hands together for them!

In this Twitter age civil rights movement, I've also learned a modest lesson about love. After Michael Brown was killed, the NAACP decided to march from the home of Michael Brown to the home of Governor Jay Nixon, 134 miles over the course of seven days. In frigid ice storms, through at least one Klan ambush, and into a small town in Missouri called Rosebud. Now, had the NAACP had a smarter CEO, he would not have called for this march in the middle of the winter time.

But we marched through an ice storm. We marched through a Klan ambush, not metaphorically, but literally, and we marched into a small town called Rosebud, Missouri. And when walking through Rosebud, Missouri, I marched beside a woman by the name of Mary Ratliff. As we marched, our fellow citizens decided to demonstrate their first amendment commitments by lifting up the N word again, and again, and again. They provided for us displays of racial animus: Fried chicken boxes, malt liquor bottles, and watermelons. And yet, a 70-year-old grandmother, walking tall in her constitutional dignity, did not respond with racial barbs, did not respond with slurs. She responded with love, kindness, and she reminded me that, yes, there were those who threatened to shoot us, yes, there were those who called us the N word, yes, there were those who reminded us in no uncertain terms how much they hated us, but she reminded me that those who sought to greet us with affection, with kindness, vastly outnumbered those who hated us. Mary Ratliff reminded me that we have to love boldly. That means you have to embrace your enemies. We have to understand that the divinely inspired grammar of humanity means that love is not a noun, it is a verb.

Love, agape love, as Dr King reminded us, "Unconditional love is not an ephemeral emotion, but an ongoing decision." Love means that you have to embrace those who hate you, be kind to those who are vile to you. May I remind you that when we went down to Mobile, Alabama, to sit in the office of Senator Jeff Sessions, they arrested us, cuffed us, mug-shot us, kept us in a holding tank for hours on end. But when I got out, I was reminded by the elderly members of that Mobile branch of the NAACP, that love of country means loving your enemies, it means walking beside your enemies, it means being in conversation with your enemies, so when Senator Jeff Sessions reached out to me within two hours of his confirmation, I took his call. And when he asked to meet with me, I met him. The point being here is this: If Martin Luther King could love Bull Connor, why can't we love our enemies in 2017? To be a civil rights activist means that you must lead with love.

We've come through a season of hate. We have seen hate crimes viciously vectoring upward, a thousand hate crimes since election day alone. Most of these hate crimes have not taken place in bars or in streets, but in our K through 12 schools. If we are going to set an example for the next generation, that means we've got to love unconditionally, we've got to care for folks unconditionally, it doesn't matter whether you like somebody, we're committed to loving everybody.

Lastly, I want to suggest to you that we have to lead bravely. We have to lead bravely. Bravery is not merely about confronting physical danger, it's about taking risk. It's about believing in your friends, believing in your colleagues, believing in your country, believing in your college enough to step outside of yourself and embrace somebody else. Lead bravely. It doesn't matter if you feel fear. It doesn't matter if you feel apprehension. It doesn't matter if you feel like you can't get out of bed in the morning. Lead bravely. Summon up from the bottom of your soul, the courage you need to lead, because so many people in this country and in this world are depending on you to lead such.

May I share with you a story about a friend of mine whose chosen name was Middle Passage. Middle Passage, a veteran of the Navy. Middle Passage, a veteran of the Vietnam War. I met him in Selma, Alabama, when the NAACP purposed to march from the home of the Voting Rights Act to the home of our democracy, Washington, DC; 1,002 miles over the course of 43 days in order to protect the right to vote. Middle Passage said to me in Selma, that he wanted to walk the entire distance from Selma, Alabama to Washington, DC. He told me that he wanted to stand up for the right to vote, that he wanted to inspire young people to join this Twitter age civil rights movement.

Middle Passage, day in and day out, faced death threats, faced the animus of our fellow citizens, but he led bravely. When we met police officers, who were not entirely happy about guarding the NAACP.

My friend Middle Passage never missed an opportunity to give a police officer a fist bump, never missed an opportunity to put his arms around a police officer, never missed an opportunity to convey with love his courage and commitment to the country. Can I tell you Middle walked 900 miles? We came to a little town called Spotsylvania, Virginia. And in Spotsylvania, Virginia, Middle Passage carried the American flag. When there was a rain storm, he wrapped the flag up. But when the rain stopped, when the clouds parted, when the blue sky emerged, Middle unfurled the flag, and when he did so, he collapsed to the pavement. My hardest day at the NAACP was explaining to a group of students that Middle didn't make it. Middle didn't come back from the hospital. Middle died. But the hardest question I've ever been asked as President of the the NAACP, was posed by those same students who asked, "If a man was willing to die for the right to vote, why can't we vote and fight for the right to vote?"

Middle's courage was not a physical courage. It was the courage to face our doubts, to face our cynicism, to face our fears. Middle stood up to cynicism, he stood up to fear, he stood up to apprehension, and so must you. Many of us will not be called to face down the Klan. Many of us will not be called to face down death threats. But all of us are called to face down our fears. All of us are called to face down apprehension. All of us are called to face down pessimism. We have to stand up and believe.

Ultimately, we must lead bravely, which means we must have the courage to hope. And if by chance, in leaving this campus, you're tempted to despair, I wanna leave you with these words that represent the hymn of the NAACP. They are entombed on a piece of faded manuscript, in the Rare Book Library on the campus of Yale University, but inscribed on the hearts of millions of members of the NAACP the world over. The words would be these, "Lift every voice and sing 'til Earth and heaven reign, ring with the harmonies of liberty. Let our rejoicing rise high as the listening skies, let it resound loud as the rolling sea. Sing a song full of the faith, that the dark past has taught us, sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us. Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, let us march on, let us march on, let us march on, let us march on. Let us march on 'til victory is won!"