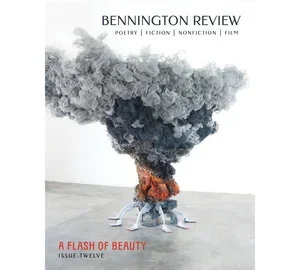

Bennington Review, Issue Twelve: A Flash of Beauty

Bennington Review—a national biannual print journal of innovative, intelligent, and moving poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and film writing housed at Bennington College—has released its twelfth issue, around the theme of “A Flash of Beauty.”

From the editor's note, by Editor Michael Dumanis and Managing Editor Katrina Turner:

“We let the plaster crack. This brings out the best in you. To be alone with beauty—wasn’t that

the prize?”

—Sylee Gore, “We Call It Time in Use”

The depressingly titled poem “Debris of Life and Mind” by Wallace Stevens begins, “There is so little that is close and warm. / It is as if we were never children.” In my twenties, I repeatedly turned to this poem when I felt despair, not because anything the poem had to say was reassuring in substance, but because the way it talked about the interior loneliness and fatigue common to adult life was so breathtakingly beautiful to me in its music, in its austere rhetorical authority, just as the macabre opening of Stevens’s “Postcard from the Volcano”— “Children picking up our bones / will never know that these were once / quick as foxes on a hill.”—is completely arresting as a composition of phonemes, the sounds rolling insouciantly over one another, language bouncing off language. I loved reading Stevens even when I had no idea what he was talking about (“Chieftain Iffucan of Azcan in caftan / Of tan with henna hackles, halt!” he writes in his poem “Bantams in Pine Woods,” overpowering me with its sound).

Some years ago, I was part of a jury charged with deciding which book of poems to publish. The manuscript that excited me most was positively word-drunk, richly layered sonically and linguistically intense. My fellow juror was more skeptical and persuaded me not to publish it. When I said, “But Sarah, read those poems out loud! That book was devastatingly beautiful,” she said, “Beauty’s overrated.” “What do you mean, overrated?” I asked, very slowly. “Face it, Michael,” she said, “It’s just assonance.”

“I stared at beauty so long / it began to lose its meaning.”

—Lara Egger, “Ars Poetica”

I was once having lunch with a visual artist who rolled her eyes at me when I described a fellow artist’s work as visually stunning. “You don’t like his work?” I asked, puzzled. She shrugged. “I just don’t get moved by the visual,” she said. “So what are you moved by?” I asked her. “Ideas,” she said, with confidence.

According to a former professor of mine, when the painter Philip Guston taught at the University of Iowa in the 1930s, he would bring a big can of paint to class with him on the first day of class and dramatically place it on his desk. “To be a painter, you first have to realize that all you have to work with is paint,” Guston said. “You think you have ideas, or images, but it’s only paint. However, paint has a terrific quality. You can mix it.” As in painting, so in poetry. In assembling this issue before you, we were startled by how many pieces of poetry and prose are aware of their materiality, how frequently they meditate on the nature of beauty or aspire to create a moment of transcendence on the page or are just, well, beautiful to see or hear or think about after reading.

It isn’t hard to imagine a counter-argument, a position that beauty is in fact “just assonance,” that someone may find beauty, like originality, not very interesting. Yes, someone may be more interested in hearing the truth than the music and doesn’t agree with John Keats that they are one and the same. In a fraught, bloody, frequently unreasonable world, what may be more significant to some is authenticity. Perhaps the very notion of beauty is a bourgeois, elite concept reeking of privilege—a lack of utility when we long for something useful, or to be useful ourselves. On the other hand, as Keats writes in his famous letter to his brother, “with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.”

“Are cormorants cruel

What are cormorants made of

What is the meaning of cormorants

How do you scare a cormorant

How long can cormorants stay underwater

Do cormorants sleep in trees”

—Mathew Weitman, “People Also Ask”

To my mind, this poem by Mathew Weitman, which I have renamed in my head the “Cormorants Exist” poem, is gorgeous in its urgent awe at the existence of cormorants, because the fact that anything exists is beautiful. The reality of a cormorant is beautiful. That people take time in their day to ask Google questions about cormorants—that’s beautiful. They’re not asking impractical questions. The creation of the poem is an inherent meaninglessness, which is what I believe makes it so powerful. I like the cormorant poem not because it’s practical, but because it’s magical. Each time I read it, it fills me with wonder; the poem feels close and warm. A flash of beauty.

The issue features poetry by Samuel Amadon, Rennie Ament, Bruce Beasley, Brittany Cavallaro, Lidija Dimkovska, Denise Duhamel, Alexandria Hall, Rebecca Hazelton, Jose Hernandez Diaz, Kim Hyesoon, Gilad Jaffe, Michael Klein, Peter LaBerge, Nick Lantz, Eugenia Leigh, Robert Wood Lynn, Lisa Olstein, Eric Pankey, Tomaž Šalamun, Elizabeth Scanlon, Nathan Spoon, Sampson Starkweather, Peter Streckfus, Rodrigo Toscano, Stella Wong, and Felicia Zamora; fiction by Marie-Helene Bertino, Emily Neuberger, and Ed Taylor; nonfiction by Kate Colby, Krystal Languell, Kathryn Nuernberger, and J. M. Tyree; a film essay by Zack Finch; and Prageeta Sharma in conversation with Michael Dumanis.