What Art Makes Possible

In this collection Tenara Calem ’15, Nancy Harrow ’52, Teresa Booth Brown ’85, and Hope Clark ’87 contribute the ways in which art has helped to expand their notions of what is possible.

Tenara Calem ’15

In the last four years since graduating from Bennington, I have learned that it is not impossible to use art as a way of solving political problems. From Theater of the Oppressed to the Center for Performance and Civic Practice, where artist/ activists creatively solve community crises using theatrical and performative methodologies, theatre and performance are helping to develop venues and processes to solve pressing problems. This is evident not only in the type of performances and spaces, but also in the trends in theatre. Today, there is a growing trend in the nonprofit theater world to hire community engagement directors whose jobs are to represent the community to the institution, and leverage the theater’s resources (teaching artists, actors, space, audiences) to meet critical and local community needs.

This past summer, I worked on a production of King Lear with Shakespeare in Clark Park, in Philadelphia to create original text with United States veterans who played Lear’s forgotten knights—building relevance between Shakespeare in Clark Park and a community that was not otherwise connected. In my work at FringeArts, I support large-scale public practice pieces in which the audience-members are the performers. This past September, we presented a massive ambulatory dance called Úumbal: Nomadic Choreography for Inhabitants, directed by Mariana Arteaga. In this piece, 50 dancers—made of residents with varying experiences in the performing arts—move a nomadic choreography through the streets of Whitman in South Philadelphia, picking up audience members as they go. My work on Úumbal brought me to build relationships with the community in civic association meetings, farmers’ markets, local businesses, radio stations, libraries, and beyond. At first this was in an effort to recruit dancers and participants for the actual show, but the neighborhood was less interested in donating five hours a week to our rehearsals as they were in seeing artists contribute to the neighborhood. Whitman is one of the most densely populated and diverse neighborhoods in Philadelphia and is currently battling against gentrifying developers excited by the neighborhood’s improvements. Instead of trying to convince neighbors to join the piece, our artistic team listened to the neighborhood’s needs. Through this dance piece, we cleaned up parks, played bingo with elders, picked up trash with neighborhood children, and went door-to-door to share this dance piece and its process.

Although I did not think it possible while at Bennington, I know now that art does not have to limit itself to simply enriching the lives of its audiences, but it can aim to improve the direct day-to-day experience of our local communities. It is why I believe that the job of an activist and the job of an artist are actually quite similar: in both roles you have to be good at getting people excited about a new possibility, getting folks out of their houses to attend an event or an experience, engaging deeply with people’s needs, and meeting them where they’re at. The questions we ask are not: were the actors skilled in their roles and did they convey the story effectively? Instead, we ask: did we respond to a need? Were we agile to feedback? When there was conflict, did we use it as an opportunity to create deeper understanding? Not all public practice pieces will be able to say yes to all of those questions. But public practice’s goal is to shift the process of artistic presentations out of “what will we say about the world around us?” to “what we will do about the world around us?”

Tenara Calem ’15 is a playwright, performer, and administrator based in Philadelphia, PA. She has worked in several capacities with companies including Woolly Mammoth Theater Company, Trinity Repertory Company, Jewish Plays Project, Horizon Theater Company, Pig Iron Theater Company, Strange Attractor, Lightning Rod Special, InterAct Theater Company, Bread & Puppet Theater, PlayPenn, and Shakespeare in Clark Park. She is a second-year playwright with the emerging playwriting lab The Foundry and works at FringeArts as the audience engagement coordinator stewarding Consensus Organizing and community engagement.

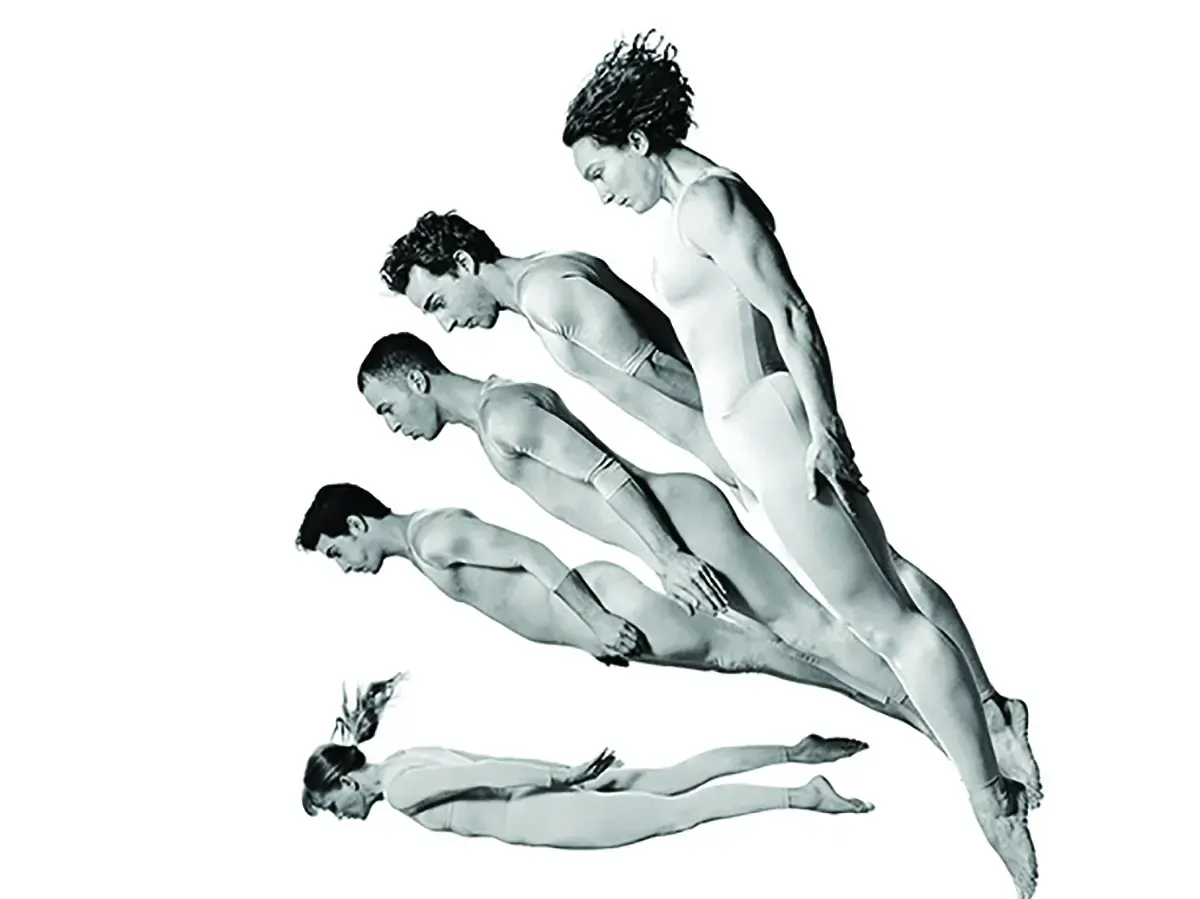

PHOTO BY JOHANNA AUSTIN

Hope Clark ’87

When I danced with Elizabeth Streb (contemporary dance choreographer and performer), we spent our days trying to do the impossible. That was our job. Imagine a move, try it, learn, try it again, and learn something new. Over and over again, until we developed the skills to master an achievement. Eventually, we were able to do what once appeared impossible, but even then, when we had achieved something repeatedly, we were working so deeply at the edge of our potential, we were never quite sure if we could really do it. I worked this way for the better part of the 1990s.

Before producers told Elizabeth her dances should be as long as a hit song, her pieces would span 20 minutes. Sometimes, we would be in the theater on opening night, and we still hadn’t been able to get through the entire dance without stopping. We would have measured stops until we could get through the entire piece. These dances were individual feats as well as collective masterpieces.

To prepare for the impossible, I wouldn’t eat for four hours before a show. I practiced yoga, touched the hardest parts of the pieces, and meditated. Despite that preparation, I still wasn’t sure if I was going to be able to get through the entire performance. Then, I would get on stage in front of an audience, and my body would show up like a racehorse. I had no idea it had that kind of power. I was astonished. What seemed impossible became possible.

Hope Clark ’87 lives on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. She founded Wheelbarrow Productions, Inc. (WHEE) partnering with communities to create social change and economic opportunities through the arts. WHEE has produced creative community projects in Ethiopia, Morocco, Palestine, and in Hope’s hometown of Chestertown, MD.

Nancy Harrow ’52

I knew I could sing, so I was not that surprised that I recorded albums of songs. But I never thought it was possible for me to compose songs, and now I have composed music and lyrics for six musicals, four of which have been produced off-Broadway and a fifth to open for a run at the Sheen Center in NYC in March 2020. Some of the others have also had runs at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, at Brooklyn Academy of Music in NYC, in Japan in translation, and at the History Theatre in St. Paul, MN. The new musical entitled About Love is a play based on a Turgenev short story. My submission is a selection of some of the songs I have written, newly recorded with young jazz musicians in 2016 and entitled The Song Is All.

Teresa Booth Brown '85

I used to think a successful artist was one of those stars whose names we all know and whose work could be seen in galleries and museums in New York. After Bennington, I worked as a teacher by day and spent my evenings painting. But the distance between my work and being a well-known artist seemed like a canyon too difficult to traverse. The idea that I could attain that kind of success, or that there were other ways of having a successful career as an artist, seemed impossible. Now I teach artists, by talking with them about their work, helping them to find their way. This aspect of my work is something I first experienced with my own teachers at Bennington. I have come to understand that the spectrum of what constitutes an artistic practice is very broad. What previously seemed impossible to me now seems infinitely expansive. There are as many ways of being successful as an artist as there are artists themselves. Teresa Booth Brown ’85 is the artist programs coordinator for the Aspen Art Museum. She teaches at the Pitkin County Jail, CO and La Napoule Art Foundation in the south of France. She is the 2019–20 recipient of the Marion International Fellowship Award for visual and performing artists.