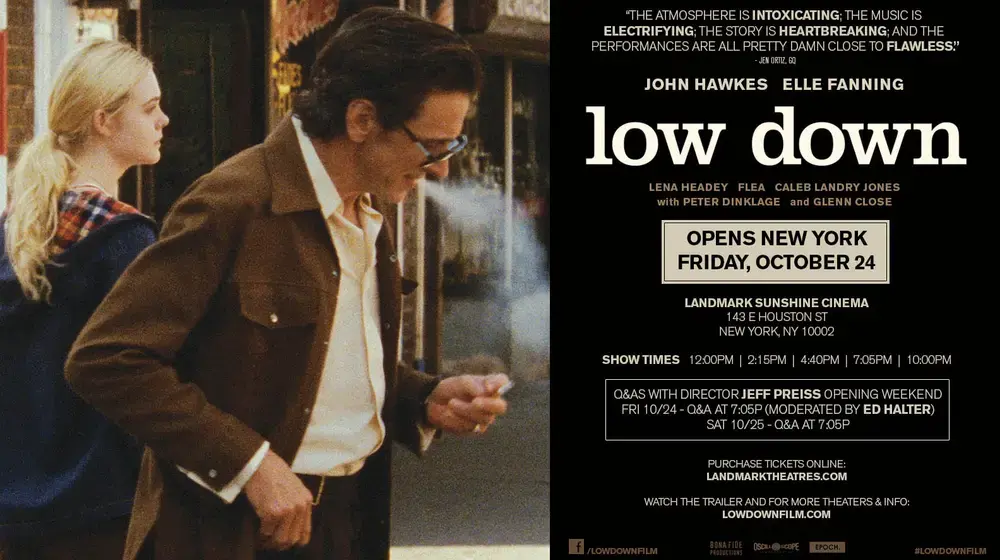

The Small World of the Low Down

An inside look at the making of Low Down by Jeva Lange ’15

After writing and co-producing the 2014 biopic on the life of musician Joe Albany, Low Down, Topper Lilien ’80 is no longer surprised by coincidences.

Directed by Jeff Preiss, Low Down serendipitously stars three former Bennington students: Peter Dinklage ’91, Tim Daly ’79 and Juliet Tondowski ’09. Topper’s former writing partner, Carroll Cartwright ’80, went to Columbia Film School in the same class as Albert Berger, who produced the film. And the Bennington coincidences don’t end there: Topper’s daughter, current student Willa Lilien ’16, just so happened to be assigned the exact same room in Franklin that Topper was given when he started college back in 1977.

When Topper told Bennington in a telephone interview that, “It seems like Low Down was meant to happen,” it comes across as an enormous understatement. Low Down certainly did have to happen; even early reviews of the film picked up on its urgency when it premiered at Sundance last January. Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan wrote that “Low Down has the feeling of a film that was meant to be.” Similarly, the New Republic called Low Down “a knockout” that is “lifted up by its cast.” The film won an award for cinematography at Sundance, and leading lady Elle Fanning received a prize for best actress at the prestigious Karlovy Vary film festival in the Czech Republic.

Although he now considers himself a screenwriter, for many years Topper had never thought of himself as a writer of anything but music: for a decade he worked as a musician, and was even offered a staff songwriting job down in Nashville. Topper and his wife were seriously considering making the move to Tennessee when, “just for fun,” Topper returned to Bennington for a summer writing workshop.

“I studied with Mary Robison, who was unbelievable, a great teacher. It was a great experience,” Topper said. “I wrote a story with Robison called ‘Mr. Fixit’ and she just fell in love with it.”

Jeanne McCulloch, an editor from the Paris Review, was also at Bennington for the workshop. Someone—maybe Robison—passed on Topper’s “Mr. Fixit” to McCulloch who, unbeknownst to him, entered it in a Paris Review contest. The story didn’t win—but it did get published. And not too much later, people were asking for the screenplay.

Working with Cartwright (who has since become the screenwriter of the acclaimed film, What Maisie Knew), Topper finished the “Mr. Fixit” script and turned down the music job in Nashville, locating instead to L.A. With that, he was officially in the movie business.

In a different corner of Los Angeles, the wheel of fate was turning. Jeff Preiss, a successful commercial director, introduced himself to a woman named Amy Albany, who was working craft services on his set.

“Amy is very striking looking, she does not look like she’s from this era, she looked like she was from the ’40s, L.A. noir—I mean she’s very attractive, wonderful. Anyway, Jeff shot this movie called Let’s Get Lost, a documentary that Bruce Weber did about Chet Baker. So he’s like, enthralled.”

Priess walked up to Amy and, out of curiosity, asked who she was.

“And Amy, if you see the movie, had a very tough childhood,” Topper explained. “So she’s stand-offish. She doesn’t really trust people easily. So finally she goes, ‘I am Amy Albany.’”

Priess then asked, “Why are you playing Chet Baker?” to which Amy replied, “Well, you know, my dad.”

“Who’s your dad?”

“You won’t know him.”

“Try me,” Preiss said.

“Joe Albany.”

Preiss’s jaw dropped. “Oh my God—Joe Albany, I love him!”

It was the beginning of a long-lasting friendship: from then on, whenever Preiss was directing a commercial, he would seek Amy out to hear more stories about the influential bebop pianist Joe Albany and his friends, Chet Baker, Terry Southern, and “all the crazy junkie stuff that was going on in Hollywood in the ’70s.” One day, Preiss asked if Amy would write it all down.

Amy was resistant; did anyone really care about her father? Preiss, frustrated, finally said, “So don’t write them down, I don’t care.”

That was all the challenge she needed. Amy began leaving Preiss notes in his trailer—notes detailing the stories she had kept pent up for so long. Soon enough, Preiss was in the possession of hundreds.

“Later,” Topper said, “Jeff [Preiss] was talking to some people about Amy at a barbeque and this one woman says, ‘Oh, can I look at the letters, I’m in publishing.’ It was Jeanne McCulloch. So what happened was, Jeff gave Jeanne the letters and she called Amy and said, ‘These are amazing,’ and put them all on the floor of her office and they fashioned them into a book.”

Since the writing seminar at Bennington, McCulloch had left the Paris Review to work at Tin House, a literary magazine based in Portland, Oregon, and Brooklyn. At the time, Tin House had just launched a book imprint, and Amy Albany’s Low Down was their first publication.

“And Jeanne McCulloch was the very woman who got me started writing,” Topper said.

Around this time, Topper paid a visit to his friend and producer, Albert Berger. Berger had been friends with Topper’s former Bennington writing partner, Carroll Cartwright, at the Columbia Film School.

“The weirdness of it is, then I end up in Berger’s office, and I see this book on his shelf,” Topper said. “It’s Low Down. And I’m sitting there talking to Albert about something else and I grab the book and I just start flipping through it. And I go, ‘Albert, this is amazing, what is this?’ and he goes, ‘Oh, we have the option for it but we can’t figure out how to make it into a movie.’ And I said, ‘I want to do it.’”

The producers were able to wrangle up the money for the film, even casting Mark Ruffalo as Joe Albany, but a grant from the State of California expired and suddenly Topper, Berger, and Preiss were strapped and Ruffalo was out.

It seems like Low Down was meant to happen

“They were going to lose it and I thought, ‘Oh no, this is pathetic, I can’t believe it, after all these years," Topper said. “I called up Albert and the director. This is not usually what a screenwriter does, but I said, ‘listen, can I just email everyone I know, call people, whatever, just let me see if I can find the money to get this movie going?’ And they said yes.”

Topper sent out between fifty and sixty emails and only got two replies. One of those was from Tim Daly ’79. Daly and Topper had worked on a script together in the ’90s, and kept in touch over the years.

“Tim said, ‘I don’t have that kind of money, are you crazy?’” Topper said. “And I said, ‘No, I know you don’t,’ but Tim does all this work in politics, I thought he might know someone. But he said, ‘No, I don’t know anyone.’ Then the next day he called me and he said, ‘I think I do know someone.’”

And just like that, the movie was back on.

In October 2014, the film premiered in New York City. In their review, The New York Times admired Low Down’s appreciation for the “in-between moments of closeness that aren’t always seen or heard.”

“[When Low Down begins], it’s like you parachuted in behind enemy lines, you’re just in this world,” Topper said. “The movie starts, and you’re in it. There’s no hand-holding. It’s just, here you are, take it or leave it.”

That’s exactly what happens: in the theater, the lights go down. Elle Fanning says, “I often thought my father was born of music, some wayward melody that took the form of a man…” And then the story begins.

Jeva Lange ’15 studies literature. She has written for Vice, The New York Daily News, and The Atlantic among other publications.