Offshoots

In this section we feature work that came to fruition as an offshoot of primary work or intended work. An actor who turns to legal performance coaching, an installation artist turned furniture maker, a publisher putting out trading cards are among the examples of work that was made in the act of improvisation and curiosity.

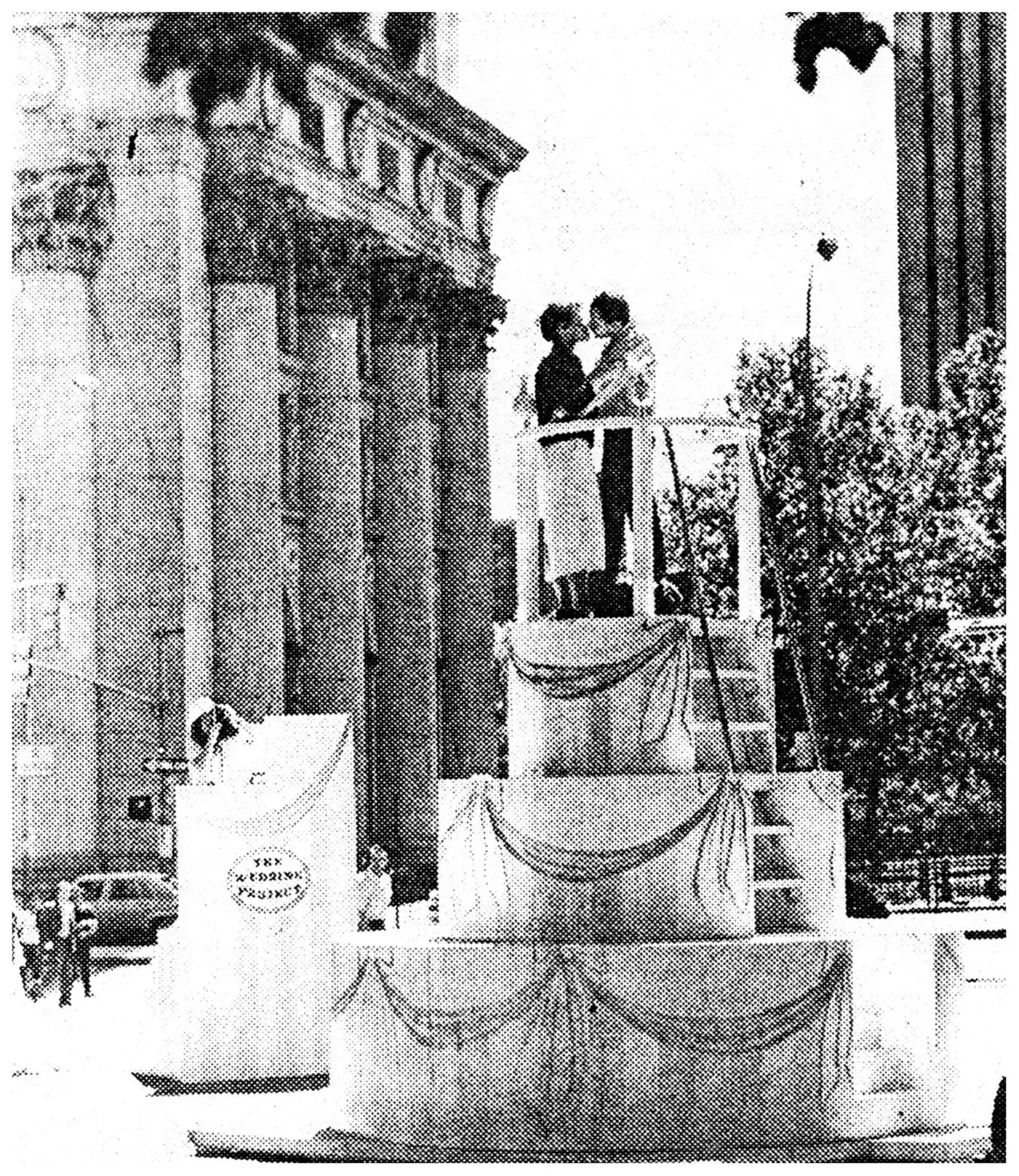

Left: A portion of bronze hardware for furnishing. Right: The Wedding Project—June 1986, I constructed a plywood wedding cake in City Hall Park. Just-married couples leaving City Hall could have their photos taken on the cake by our photographer. Each couple was given a photo, and another was kept for the project archive at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, which sponsored the project.

Barbara Ross Greenberg ’69

When I lived in New York I made things that were intended to disintegrate; my focus was on the process, and the pieces had a natural life, and ending, of their own. When I moved to the Netherlands in 1991, I was permitted to earn money only by selling what I made. I met this challenge by returning to work that I had done earlier, making bronze furniture and hardware to suit specific clients and situations: a table with two squirrels for a banker, a lamp with four monkeys for a family with four children, a set of magnolia seedpods as cabinet pulls for someone who collects magnolia trees, and so on. I take great pleasure in knowing that the work I make becomes part of my clients’ daily lives.

Jane Wechsler ’66

I never thought I’d be a teacher, nor did I think I would ever open a school, but that’s exactly what I did when I founded the Montessori Family School, Berkeley, CA in 1981. The influence of my own teachers from grade school to Bennington was apparent when I hired Montessori teachers. Our art teacher was a working artist. Our music teacher played in a band. The children could see their teacher’s work around the school and in shows throughout the community. Nothing was dogmatic. Everything was alive. The essence of learning and teaching. My children attended the school and now my three granddaughters attend as well. The grace of this life has been to spend it in service to what I love the most.

Gillian Drake Angle Moorhead ’76

Left: After graduate school in theatre directing, I moved to Washington, DC and began my long career in theatre. While working at Arena Stage, I had to supplement my income by giving voice lessons to actors and singers. But I got the idea to expand my theater expertise to lawyers and then to their witnesses. In the basement of the Old Vat Room at Arena Stage, I started a class called “Acting for Lawyers.” The class got a lot of publicity and eventually became my prime source of income. At the time, few people were doing this and I ended up contributing to the creation of a new branch of theatre work called “Applied Theater Skills.” These days, it’s a hot space. For my part, I developed a new role on legal teams: witness preparer. This began a kind of cottage industry of other theatre artists around the country who would start to learn to coach lawyers and a few others to prepare witnesses.

Mary Meriam ’78

Center: I created Headmistress Press in 2013 to publish poetry books by lesbians. We hold an annual Charlotte Mew Chapbook Contest and produce Lesbian Poet Trading Cards, which were featured on AfterEllen and on Harriet, the Poetry Foundation’s blog. Head over to headmistresspress.blogspot.com to learn more about us. (Center)

Margaret Rizzio ’09

Right: I create one-of-a-kind, multilayered collages sourced from magazines and ephemera. I am inspired by the euphoric colors and ubiquitous imagery of the “perfect woman” used in print in the 1940’s, 50’s and 60’s. I made these limited-edition towels to expand my audience, and create democratic multiplies, an idea discovered and embraced in the Bennington print shop.

Sandy Sorlien ’76

Before I set off into the brambles to do it, no one had photographed the entirety of the abandoned 108-mile Schuylkill Navigation slackwater- canal system. I did hear from a guy whose license plate reads “CANLNUT” that he had photographed all the sites, but he wouldn’t show me. Pictures or it didn’t happen!

The Schuylkill Navigation, chartered in 1815 and opened in 1825, carried anthracite coal from the mountains of Schuylkill County to downstream markets, and to tidewater below the Fairmount Dam in Philadelphia. This coal, along with waterpower from the canals, literally powered the Industrial Revolution in southeastern Pennsylvania and beyond. But compared to the Erie Canal that opened a few months later, the navigation is not well known even in our region. Five of the sites are listed on the Historic Register, but most of the locks, aqueducts, and canals are hidden on private property. Twenty-eight of the 32 dams were dismantled, and many locks were buried by a massive river- dredging project in the 1950s. Yet plenty of the stone infrastructure can be studied, if you’re willing to trespass and bushwhack, or get in a boat.

My book Inland: The Abandoned Canals of the Schuylkill Navigation is currently in the design phase. The research phase was supported by the Fairmount Water Works, where I’ve been employed as an educator, researcher, and photographer since 2013.

In Place of Now, an exhibition co-curated by Rone Shavers ’93, professor of English at the College of Saint Rose in Albany, NY was shown at the college’s Opalka Gallery this spring. The show, which was devoted to Afrofuturism, drew on Shaver’s expertise in history, literature, and culture and featured the work of eight African-American artists.

Riva Poor ’56

In 1968, I had a husband, children, a full-time job, and was in graduate school at MIT. Fortunately, my bosses allowed me to flexible hours to accommodate my schedule. In 1970, I read about how Kyanize Paint Co. had changed its schedule from the standard five eight-hour days a week to four nine-hour days, thereby increasing its profits while giving its employees three- day weekends. Wow! I thought such scheduling innovations called for a book. That summer, I organized several experts to write about the innovation. I profiled three dozen companies on various new schedules, wrote several chapters, edited my co-author’s chapters, and four months later published the book, 4 days, 40 hours: Reporting a Revolution in Work and Leisure. The media gave the book a lot of attention, and a tidal wave of companies adopted new schedules designed specifically for their work and workforce. Today more than 50 million Americans have what we now call flexible work weeks. In 1971, on graduating MIT, many companies would not hire women with MBAs. Billing myself as a “Professional Problem-Solver,” over the next 25 years I solved problems for more than 200 companies and 2500 individuals. I have recently finished writing a book, Raising an Innovator, foreword by Nobel Laureate Paul A. Samuelson, illustrating how my parents reared me and how I created a number of problem-solving techniques, including one for eliminating self-defeat.